Ancel Keys and the Seven Countries Study

Ancel Keys was one of the first researchers to contribute substantially to the study of the link between diet and cardiovascular disease. Sadly, there is a lot of low-quality information circulating about Ancel Keys and his research (1). The truth is that Keys was a pioneering researcher who conducted some of the most impressive nutritional science of his time. The military "K ration" was designed by Keys, much of what we know about the physiology of starvation comes from his detailed studies during World War II, and he was the original Mediterranean Diet researcher. Science marches on, and not all discoveries are buttressed by additional research, but Keys' work was among the best of his day and must be taken seriously.

One of Keys' earliest contributions to the study of diet and cardiovascular disease appeared in an obscure 1953 paper titled "Atherosclerosis: A Problem in Newer Public Health" (2). This paper is worth reading if you get a chance (freely available online if you poke around a bit). He presents a number of different arguments and supporting data, most of which are widely accepted today, but one graph in particular has remained controversial. This graph shows the association between total fat intake and heart disease mortality in six countries. Keys collected the data from publicly available databases on global health and diet:

The graph shows that there was a very strong positive correlation between total fat intake and reported heart disease mortality among the six countries Keys selected for his analysis. Critics Yerushalmy and Hilleboe later pointed out that data for 22 countries were available at the time of Keys' analysis. When all 22 countries were considered together, the relationship between total fat intake and heart disease mortality weakened but remained statistically significant (3).

These data, among others, stimulated Keys to design the most ambitious diet-heart study ever conducted at the time: the Seven Countries Study. This study investigated the link between diet, lifestyle, cardiovascular risk factors, and disease risk among 16 populations in 7 countries.

Keys' diet assessment methods were extremely rigorous. To determine the food and nutrient intake of each population, for one week his team invited selected families to prepare duplicate meals: one for themselves, and one for the study. The extra meals were then weighed and chemically analyzed to determine their nutritional characteristics. This method is far more rigorous that the questionnaires used in most observational studies today.

However, the study design suffered from a critical weakness: Keys' team used data from 20-50 people to extrapolate the average dietary intake of the population as a whole, and these average population data are what they used for their analyses. In other words, rather than comparing the dietary intake and cardiovascular risk of individuals, the Seven Countries Study compared the dietary intake and cardiovascular risk of populations. This is called an ecological study and it's considered to be a weaker study design than the numerous individual-level observational studies that followed it.

What did Keys' team find? Here are some of their main findings:

- Circulating cholesterol was strongly correlated with cardiovascular risk.

- Dietary saturated fat intake was strongly correlated with circulating cholesterol.

- Dietary saturated fat intake was strongly correlated with cardiovascular risk.

- Animal foods were the primary source of dietary saturated fat.

- Meat intake, except fish, was correlated with cardiovascular risk, although that was mostly explained by its saturated fat content.

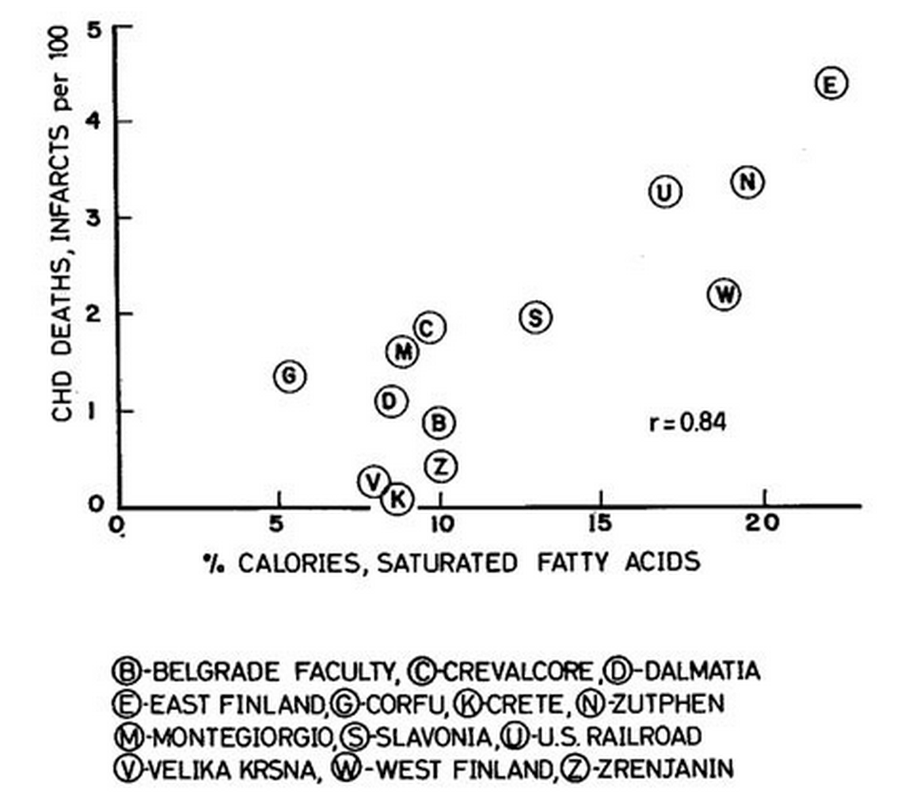

The graph below is from a 1970 paper detailing the relationship between saturated fat consumption and 5-year risk of heart attack mortality among most of the populations of the Seven Countries Study (4):

This is a very strong correlation showing that populations that eat more saturated fat have more heart attacks, and it was confirmed in a 25-year follow-up study of the same populations (5).

The lowest cardiovascular risk occurred on the rural Greek island of Crete, and a rural Japanese farming community at Tanushimaru. At the beginning of the study, both cultures ate starchy omnivorous diets relatively low in animal foods and high in grains and potatoes (6). The diet at Tanushimaru was very low in fat, whereas the Cretan diet was moderate in fat, mostly from extra-virgin olive oil but also from dairy. The diet of Crete was low in meat and fish but averaged about one cup of milk per day and 3 medium eggs per week. The diet at Tanushimaru averaged 1/5 lb of fish per day and 2-3 medium eggs per week. Both cultures consumed polyphenol-rich plant foods such as extra-virgin olive oil and green tea, and exhibited the various lifestyle factors typical of non-industrial cultures (e.g., regular physical activity, sun exposure, absence of processed foods, slower pace of life).

Blue Zones

The diets of Crete and Tanushimaru are consistent with the diets of populations that live in so-called "Blue Zones"-- areas of notably low cardiovascular disease risk and long natural lifespan (7). Blue Zone populations typically eat meat, and often dairy and eggs, in small to moderate quantities (significantly less meat than is typical of affluent Western cultures). There is one Blue Zone in Loma Linda, California, that contains a high proportion of vegetarians, but the other populations all eat meat. None of the Blue Zones are vegan. The diets in these areas are centered around carbohydrate, and more often than not, grains and legumes of some sort. This doesn't prove that their food choices are optimal, but it does prove that such diets are, at a minimum, compatible with health and long life in the context of a more traditional lifestyle.

Non-industrialized Agriculturalists and Hunter-gatherers

The populations with the lowest documented cardiovascular risk are agricultural (and horticultural) cultures living a traditional lifestyle that resembles how our ancestors might have lived 5,000 years ago. In an impressive heart autopsy study on thousands of subjects, Lee and colleagues determined that rural West Africans (Nigerians and Ugandans) in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s were essentially immune to heart attacks, even in old age (8). Their coronary arteries also exhibited less atherosclerosis than Americans, including African-Americans. In the same study, urban Asians living in Japan and Korea had a lower rate of heart attacks than Americans, but higher than Africans. A number of other studies have reported similar findings in various traditionally-living agricultural/horticultural societies (9, 10, 11, Trowell and Burkitt. Western Diseases. 1981).

These cultures tend to eat a starch-based omnivorous diet low in animal foods. It's possible that the Nigerian and Ugandan samples may have included some pastoralists with a high intake of animal foods, but the vast majority of people would have followed a starchy low-animal-food diet. The dietary pattern in these agricultural/horticultural cultures may not be the only factor in their resistance to heart attacks, but their diets are at least compatible with exceptional cardiovascular health.

We have much less information about traditional cultures that eat diets higher in meat, for example, most hunter-gatherers. The only autopsy studies we have of hunter-gatherers were performed in a few Inuit (Eskimo) individuals, and they suggest that these individuals tended to suffer from advanced atherosclerosis but that no signs of heart attack are present (12, 13). Atherosclerosis did not appear to translate into a high heart attack risk in semi-traditional Inuit populations that have been studied, suggesting that they may have somehow been protected from the consequences of their vascular disease (14). In any case, the Inuit are probably not representative of hunter-gatherers in general because they ate extreme diets, lived in an extreme environment, and inhaled a lot of indoor smoke.

Although we don't have autopsy studies in more typical hunter-gatherer cultures, we do have some information about their cardiovascular health. Hunter-gatherers invariably show evidence of good cardiovascular health, including low body fatness, low cholesterol, low blood pressure that doesn't rise with age, and high physical fitness (15, Trowell and Burkitt. Western Diseases. 1981). It would be difficult to imagine a high cardiovascular risk in these populations that rely heavily on meat (16), but again we have little direct evidence of this.

The China Study

The China Study was a massive ecological study relating diet and lifestyle to chronic disease risk in China. It has been invoked by researcher and vegan diet advocate Colin Campbell to support the idea that animal foods promote cardiovascular disease and cancer, even in the small quantities that were typical of the regions studied. After having reviewed the study data, the publications based on it, and the various commentaries on it, it appears relatively clear that the China Study does not support the conclusion that meat consumption is associated with cardiovascular disease or cancer risk (17, 18, 19, 20, 21). Everyone seems to agree on that, except Campbell and certain other vegan diet advocates. I won't discuss the China Study further.

Modern Observational Studies

What do modern observational studies have to say about the relationship between meat intake and cardiovascular risk? Overall, they paint a substantially different picture than the Seven Countries Study. Here is a summary of the weight of the evidence, as I understand it:

- Total meat, saturated fat, and dietary cholesterol intake typically show little or no relationship with circulating cholesterol, over 2-3 fold differences in intake (22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28). It remains unclear whether this reflects a lack of a long-term causal relationship, or limitations of the study methods.

- Total saturated fat intake is not associated with cardiovascular risk (29).

- Intake of eggs and dairy (whether full-fat or reduced-fat) are not associated with cardiovascular risk (30, 31).

- Intake of seafood is typically associated with reduced cardiovascular risk (32).

- Intake of poultry is associated with neutral or reduced cardiovascular risk (33).

- Intake of fresh red meat is inconsistently associated with higher cardiovascular risk (34, 35), although meta-analyses suggest the effect size is small.

- Intake of processed meat (e.g., hot dogs, bacon, salami) is typically associated with higher cardiovascular risk (36).

Because these findings are observational and most rely on relatively inaccurate food questionnaire data, we have to take them with a grain of salt. However, my understanding is that most epidemiologists would weight them more heavily than the Seven Countries Study, at least when it comes to deciding what we should eat as individuals. If you are an epidemiologist and you disagree with that statement, please share your thoughts in the comments.

The Harvard Healthy Eating Pyramid is based primarily on a synthesis of this observational evidence (37). It recommends eating fish, poultry, eggs, and 1-2 servings per day of dairy, but advises limiting red meat, processed meat, and butter. Whole grains, plant oils, and vegetables/fruits form the base of the pyramid, and nuts, seeds, beans and tofu are recommended, particularly as an alternative to red meat. It's notable that the Healthy Eating Pyramid includes meat as a staple food.

Do Vegetarians and Vegans Have Fewer Heart Attacks than Omnivores?

Overall, yes. Although not all studies have supported this conclusion, the weight of the evidence suggests that vegetarians and vegans have a lower heart attack risk than omnivores (38). Risk among lacto-ovo vegetarians, vegans, and seafood eaters appears similar however (39). If we assume for a moment that these associations reflect cause and effect, there appears to be little to gain from completely avoiding animal foods or even avoiding all types of meat.

Many Seventh-Day Adventists avoid eating meat for religious reasons, although they typically eat eggs and dairy. There's a large population of SDAs in California that researchers have studied extensively. These studies demonstrate that SDAs have a substantially lower heart attack risk than the general population, and SDAs that are vegetarian have a lower risk than SDAs in the same community that eat meat (40). Vegetarian SDAs are also noted for their longevity.

Many Seventh-Day Adventists avoid eating meat for religious reasons, although they typically eat eggs and dairy. There's a large population of SDAs in California that researchers have studied extensively. These studies demonstrate that SDAs have a substantially lower heart attack risk than the general population, and SDAs that are vegetarian have a lower risk than SDAs in the same community that eat meat (40). Vegetarian SDAs are also noted for their longevity.

Studies of vegetarians and vegans aren't easy to interpret, however. Vegetarians and vegans differ from the general population in many ways besides meat avoidance, and this is particularly true of SDAs. These populations tend to be more health-conscious and have overall healthier lifestyle behaviors. Can we determine how much of their cardiovascular advantage is due to meat avoidance, and how much is due to factors unrelated to meat?

The Health Food Shoppers Study attempted to tease this out. This UK study recruited vegetarians and omnivores from health food stores and vegetarian societies and magazines-- ensuring that both groups were composed of health-conscious people. After 17 years of follow-up, the results showed no statistically significant difference in total mortality, heart attacks, or stroke between vegetarians and non-vegetarians, although there was a trend toward lower heart attack risk for vegetarians (41).

Overall, the evidence suggests that factors other than meat avoidance account for at least some of the cardiovascular benefit associated with vegetarian and vegan diets. However, there may still be some cardiovascular benefit from avoiding meat, and this would be consistent with the LDL-lowering effect of meat avoidance (discussed below). The observational evidence does not appear to support the idea that avoiding seafood, dairy, or eggs reduces cardiovascular risk.

Vegan Diet Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease

Dean Ornish, Caldwell Esselstyn, John McDougall, and others have used vegan or near-vegan diets as part of a diet, lifestyle, and/or drug strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in high-risk patients. Some of them have published studies (42, 43, 44). These studies vary in quality, but overall they do suggest that these diet/lifestyle/drug strategies may indeed be effective for reducing cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients (typically, people who have had a heart attack or have been diagnosed with severe cardiovascular disease). They are probably more effective than conventional medical therapy.

However, it's difficult to know what aspect of the intervention is responsible for the cardiovascular benefits. Ornish's intervention, for example, involves a comprehensive diet overhaul including reducing fat intake, avoiding processed food, focusing on minimally refined foods, and increasing vegetable intake. The intervention also includes smoking cessation, regular exercise, and stress reduction. Esselstyn's intervention is not quite vegan but it excludes nearly all dietary fat and includes lipid-lowering statins for patients who aren't able to meet stringent blood lipid goals through diet alone.

What role does meat avoidance play in these results? Are patients benefiting from reducing their intake of processed and high-heat cooked meat? Are patients benefiting from reducing their intake of red meat? Are patients benefiting from reducing their intake of all types of meat? There are a lot of remaining questions here, and these studies are not able to answer them.

It is plausible that animal food avoidance could play some role in the therapeutic effect of these diet and lifestyle strategies, but the studies don't allow us to come to that conclusion. There are too many confounding factors. It would be informative to study the effectiveness of these interventions with or without added meat.

Animal Studies and Possible Mechanisms

Beginning with the pioneering studies of Nikolay Anichkov in the early 1900s, researchers have long known that high levels of dietary cholesterol can rapidly promote cardiovascular disease in certain animals. Dietary cholesterol in the human diet comes exclusively from animal foods, with egg yolks being the most concentrated source, so dietary cholesterol is an obvious suspect in the possible link between animal foods and cardiovascular disease.

These artery-clogging high-cholesterol experimental diets generally cause massive 3-10-fold increases in circulating cholesterol in animal models, which is difficult to compare to the human situation. Humans only see small increases in circulating cholesterol when we eat dietary cholesterol, and the increase typically occurs in both "bad" LDL and "good" HDL* (45). Most humans seem to be able to handle normal amounts of dietary cholesterol efficiently, which substantially weakens the likelihood of a meaningful link between dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. However, in a minority of people, dietary cholesterol has a larger effect on circulating cholesterol, and could play a larger role in cardiovascular risk.

Saturated fat is another possible link between animal food consumption and cardiovascular risk. In typical Western diets, most saturated fat comes from animal foods. Saturated fat feeding can exacerbate the impact of high-cholesterol diets on circulating cholesterol and cardiovascular damage in animal models, at least when compared with polyunsaturated fat (the latter of which has a cholesterol-lowering effect). However, when animals are not overfed cholesterol, saturated fat feeding per se doesn't raise circulating cholesterol when compared with monounsaturated fat (as in olive oil), so I'm not sure to what extent saturated fat itself is responsible (46, 47).

In humans, many trials have shown that short-term saturated fat feeding increases circulating cholesterol. This increase occurs in both the LDL and the HDL fraction, although the increase in LDL is often somewhat greater than the increase in HDL (48). However, the fact that observational studies typically find little or no correlation between habitual long-term saturated fat intake and circulating cholesterol (or cardiovascular risk) makes me wonder how durable these effects are (49). Longer-term randomized controlled trials also often show little or no impact of 2-3-fold differences in saturated fat intake on circulating cholesterol, as long as other relevant dietary components including linoleic acid (n6 PUFA) and fiber are kept relatively constant (50). Research is ongoing, but I'm not currently convinced that this mechanism plays a major role in cardiovascular disease.

High levels of animal protein (from meat or dairy) can increase LDL cholesterol and aggravate cardiovascular disease in certain animal models, while plant protein is often protective (51). This appears to be due to the amino acid composition of animal vs. plant protein (lysine-to-arginine ratio), and the phytochemicals and fiber associated with plant protein. Certain plant proteins, such as soy, also tend to lower LDL cholesterol in humans, particularly when they replace animal protein (52, 53). This probably goes a long way toward explaining the LDL-lowering effect of vegetarian and particularly vegan diets, and it is consistent with a protective cardiovascular effect.

Another potential mechanism for harmful effects of meat is the compounds that are produced during high-heat cooking. Some of these may be carcinogenic and contribute to cardiovascular disease (54). We might be better off focusing on low-heat-cooked meat rather than grilled, browned, roasted, or fried meats-- but this also applies to plant foods.

Red meat is very high in iron, which some researchers have proposed could compromise cardiovascular health. Free (unbound) iron is particularly good at catalyzing powerful free radical reactions that damage surrounding molecules. While iron is an essential nutrient and high-iron foods can be particularly beneficial for pre-menopausal women, many men and post-menopausal women may get too much dietary iron. Personally I think excess dietary iron is probably detrimental to overall health, but the evidence is not currently very convincing that body iron status plays a major role in cardiovascular health in particular (55, 56). The case isn't closed yet.

Sialic acids are unique sugars that are used as building blocks for certain classes of molecules in the body. Over the course of evolution, humans have lost the ability to produce a particular sialic acid called Neu5gc. However, we absorb it from animal foods, particularly red meat, and it is incorporated into our (glyco)proteins and other molecules. The human body recognizes it as foreign and produces antibodies against it. Some researchers have proposed that the immune reaction that the body mounts toward Neu5gc from meat causes inflammation and contributes to disease risk (57). Although the paper introducing this mechanism made a big splash when it was first published, to my knowledge the finding hasn't been followed up sufficiently to make a compelling case that Neu5gc actually contributes to human disease. Perhaps future research will clarify that.

There are many scary-sounding mechanisms by which meat intake could potentially contribute to disease. However, I'd like to point out that you can find something wrong with any food if you look hard enough. Melissa McEwen illustrated this well in her satire piece "Just Kale Me". Mechanisms are relevant, but they only serve to explain or bolster demonstrated effects. For example, if poultry consumption doesn't actually increase cardiovascular risk, there's no point digging around for mechanisms. When they have been identified, mechanisms can increase our confidence in an empirically demonstrated effect on health.

There is a lot of evidence we can bring to bear on this question, and not all of it is consistent. This inconsistency is why we see different groups interpreting the research in opposite ways.

Here is my best attempt to synthesize the overall evidence, as I see it. Vegetarian and vegan diets probably do reduce cardiovascular disease risk, consistent with the LDL-lowering effect of replacing meat with plant protein. However, the risk reduction afforded by avoiding meat per se appears modest (as opposed to living the whole lifestyle of a vegetarian or vegan), and we have no examples of healthy vegan cultures. There is little evidence that poultry or seafood promote cardiovascular disease, and some evidence suggesting that seafood is actually protective. Although the evidence on red meat isn't very consistent, and we need more and better research, it's probably prudent to keep intake modest for now. It's probably a good idea to limit processed meat intake as well (attn LCers and Paleos: bacon).

For people at high cardiovascular risk, it may be useful to replace some animal protein with plant protein such as beans and nuts, and focus meat intake on seafood and poultry. Randomized controlled trials such as the Oslo Diet-Heart study have supported the ability of similar dietary patterns to reduce cardiovascular risk (58).

The ideal strategy would also incorporate other factors that are relevant to cardiovascular risk, such as controlling body fatness, eating potassium- and polyphenol-rich fruit and vegetables, focusing on unrefined food, exercising regularly, avoiding prolonged sitting, managing stress, avoiding cigarette smoking, and working with a doctor to monitor and possibly control blood pressure and lipids.

So, does eating meat increase cardiovascular risk? Yes! And no!

In the next post, we'll examine the impact of meat consumption on obesity risk.

* Nuance: we know that people with high HDL cholesterol have fewer heart attacks, but we still don't know whether a diet-induced increase in HDL cholesterol is actually protective. Recent drug trials have shown that using drugs to simply pack more cholesterol into HDL particles does not reduce cardiovascular risk in humans, and it may even increase risk. This demonstrates that the protective function of the HDL particle is not always associated with its cholesterol content. We still have a lot to learn about why high HDL cholesterol is associated with cardiovascular protection in humans, and what diet/lifestyle factors influence its protective actions.

33 comments:

Hey Steven,

As far as the mechanisms of heart disease are concerned, you might be interested in reading some of Mr. Heisenbug's posts on the gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease.

Basically, smoking and eating a diet low in plant fiber are two of the risk factors for heart disease, and the same compositional change to the gut microbiota happens in both of those populations.

The reason this is important to the discussion on meat and cardiovascular disease is that in Western societies, meat and the dreaded fat often replace foods high in fiber that would otherwise promote a healthier composition of the gut.

Food for though! Love your blog posts! I will be looking forward to the next installment of this series.

Austin

Fantastically written article. I oftentimes become bogged down in the numerous analyses of different studies by different groups and long for a rational, cohesive conclusion. Will that ever happen considering the sheer complexity of biochemistry that is the human organism? That remains to be elucidated.

A few plural/singular errors in text -- e.g.

“Intake of eggs and dairy (whether full-fat or reduced-fat) are not associated with cardiovascular risk (30, 31).”

You say: "However, the fact that observational studies typically find little or no correlation between habitual long-term saturated fat intake and circulating cholesterol (or cardiovascular risk) makes me wonder how durable these effects are"

This is often the case when you look at saturated fat consumption and cholesterol levels within a population. You may actually expect that the correlations are zero, since the inter-individual variation is so large that it dilutes any real correlation. Plus, cholesterol levels are of course also affected by many other factors, which further dilute the correlation with saturated fats. Jacobs et al. (1979) is one paper that discuss this: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/313701.

I will also (again) remind about Geoffrey Rose's proposition that in populations with a homogenous fat intake of fat, other factors than fat determines why some have high cholesterol or not.

In that regard, I find the Oxford Vegetarian study interested. The participants were self-described vegetarians and their non-vegetarian friends and relatives. After about 13 years of follow-up, the RR for the highest tertile of animal saturated fat was 2,77 for IHD. The authors note:

“Most other cohort studies have involved more homogeneous populations with a relatively narrow range of fat intakes. It is impossible to identify even strong disease associations if there is little variation in a dietary variable in the study population”.

The focus on heart disease to the exclusion of everything else shows, if nothing else, the culture funding the experiments (e.g. white, middle-aged Congressmen and bureaucrats who are prime aged for dying of heart disease). Often left out of these discussions are all of the other diseases, such as cancer and diabetes, that cause much more horrific deaths. Does it matter if vegetarians have less heart disease if they have more cancer (not saying they do; I don’t believe the question has been satisfactorally aswered in a way that isn’t confounded by the complier effect)? That it hasn’t been answered is kind of the point.

Even within the world of heart disease, LDL and HDL are horrible biomarkers with little to no predictive power (HDL to trigs ratio probably being the best, but, as you mention, hard to know if altering it actually alters risk), so optimizing for those seems absolutely silly, yet even your article focuses heavily on LDL, a biomarker only talked about because pharmaceutical companies had drugs available that lowered it.

In the end, the method of dietary research where we focus on single items just seems inane. We are incredibly complex biochemical machines requiring a dizzying array of inputs. In the 1950s, we believed anything nature could do, man could do better. Now, having been suitably kicked in the croch by that hubris, perhaps it’s time to back off and look at what our ancestors ate, and not Greek and Italian peasants in a war-torn economy.

My ancestors all ate copious amounts of meat, since they all came from far northern Europe. I was unhealthy all of my life until I decided to say screw all of the experts and experimented on myself with my own “ancestral” diet. Now, for the first time ever, my body manages itself (ideal weight, ideal blood sugars, ideal (if useless) cholesterol numbers, etc).

So, perhaps instead of believing something is “good” or “bad” for everyone, we should believe a little more in the abilities of nature of optimize genetics, so a northern European “perfect” diet is going to be different from a Pacific islander’s diet. Even if there isn’t a single “perfect” diet, we can be pretty confident that anything that is processed to the point that it can sit on shelves for an indefinite amount of time, thereby not able to feed even bacteria, cannot be part of anybody’s healthy diet.

Stephen

Here's a link to the full study

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1922056/pdf/canmedaj01034-0002.pdf

The Geographic Pathology of Coronary Atherosclerosis

R. F. SCOTT, M.D., A. S. DAOUD, M.D. and K. T. LEE, M.D.,

Question about "processed" meats: Can you shed any light on what aspect of processing makes them detrimental? For instance, we smoke quite a bit of meat at home (venison and pork, mostly in dry sausages and jerkies--we don't cook it except for the smoking process). I'd like to have a sense of what causes the health problems--grinding it up, using smoke, adding preservatives, aging it, cooking it, the fact that many commercial processed meats are low-quality, etc. I'm guessing there's not a lot of evidence either way about this, but I'd love to hear any thoughts you have, since this is a significant portion of the meat we consume. Thanks for your time, and for putting this series together!

Nice post, looking forward to the rest. Just had a comment on the Health Food Shoppers study.

I follow the blog of Jack Norris RD, a vegan dietitian. He has written that Health Food Shoppers is one of the weakest cohort studies available on vegetarians. He quotes this part of the paper:

"Another limitation is that the questionnaire was short and did not include several important food groups (for example, dairy products, fish, alcoholic drinks), did not allow us to estimate energy intake, and did not include other factors known to be associated with health (exercise, socioeconomic status, past smoking habits). We were therefore unable to explore whether the significant associations observed were partly due to confounding by other dietary or non-dietary variables."

http://jacknorrisrd.com/response-to-chris-kessers-why-you-should-think-twice-about-vegetarian-and-vegan-diets/

Thanks for this thorough post on meat. You have gone through huge amount of literature. I’m very happy you wrote this because I know many of your readers (and mine too) are arguing red meat is as healthy as food can get. I agree with most of your conclusions.

I do not comment on the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cancer because I assume you may touch upon them later.

Intake of saturated fat increases circulating cholesterol levels even if some cohorts may miss this link. This is thoroughly studied subject in randomized trials. First, as you say, there is huge amount of short term feeding trials (Clarke R et al. BMJ 1997, meta-analysis of 395 trials) showing clear causal effect. Furthermore, many classic fat replacement trials such as Oslo Diet Heart, Finnish Mental Hospital and Rose Corn Oil Studies etc. show clearly that the effect is durable over several years. The cholesterol reduction was approximately 12-20% in these studies.

In my opinion, the notion that saturated fat intake is only weakly correlated to circulating cholesterol levels in cohort studies should not be used as primary evidence because more powerful research designs, ie. RCTs, show actually a causal relationship. Second point on this, ecologic data from Finland, Sweden and US demonstrate the association between reduced saturated fat intake and cholesterol levels. I can point out the references if needed.

I think more focus should be put on possible other factors than saturated fat, as you state. I agree with you, too much iron is not good for health. Heme iron, AGEs and fermentation of unabsorbed protein (microbiome effect) may explain some of red meat’s effects on cardiovascular health. Red meat, especially beef, is very rich source of heme iron. Heme iron intake is associated with cardiovascular disease in newer meta-analyses (Hunnicutt et al. J Nutr 2014 & Yang et al. Eur J Nutr 2014). You refer to an iron meta-analysis from 1999.

I would like to also add that processed meat (includes cold cuts like ham or turkey/chicken) is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular *mortality* in two recent meta-analyses. Effect sizes are rather small though in these analyses. (O’Sullivan et al. Am J Public Health. 2013 & Abete et al. Br J Nutr 2014 ).

Finally, a recent meta-analysis in Asian countries ,where the consumption of beef is very low compared to US, red meat was associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality in males but not in females (Lee et al. AJCN 2013). Perhaps this really is a question of dose.

Already looking forward to the next part.

I always thought it was fairly simple: In most of the trials they looked at increased PUFA and decreased SFA but then erringly they pointed at SFA being the culprit of the change in CHD when there were two factors changed.

So instead of SFA increasing CHD the PUFAs decreased CHD. Trials where SFA was replaced with carbohydrates lends credence to that since those showed no change in CHD.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2950931/

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2676998/

Hi Reijo,

Thanks for your comments. Regarding the SFA-cholesterol connection, I'd like to point out that the trials you cited increased PUFA intake substantially, which is known to lower cholesterol. I recognize that many diet-heat RCTs showed durably reduced cholesterol, but all of them increased PUFA intake. That's why I find the 6 mo RCT I cited particularly informative-- they reduced SFA intake without a large increase in PUFA. The ecologic studies you mentioned also involved increased PUFA (correct me if I'm wrong). In the US, our cholesterol has decreased over the last few decades despite no change in SFA intake. The reason is probably that we've doubled our n6 intake from seed oils.

If SFA has a significant and durable impact on circulating cholesterol, the association should be readily observable using an observational design, as long as the measurements are accurate. The banker's study I cited in my article was one such study. They used one-week weighed food records and multiple (total) cholesterol measurements, and were unable to find any association whatsoever between SFA intake and TC, even over several-fold differences in SFA intake and large individual differences in circulating cholesterol. There was not even a trend toward an association. Personally, I find that to be a relatively strong piece of evidence.

I recognize that there is evidence supporting a link between SFA intake and increased cholesterol, including short-term RCTs and animal cholesterol feeding studies. However, it's difficult for me to accept the hypothesis when there is little or no detectable long-term association between SFA and TC/LDL even in studies that used accurate measures of each. If this effect is as significant as claimed, it should be readily detectable in observational studies. If you believe that there's no association between SFA intake and CHD events, then this would readily explain the lack of association.

I reserve the right to change my mind about the SFA-TC/LDL link, but I would need some sort of compelling explanation for why the effect is not observed in most observational studies or in longer-term RCTs.

One possible explanation is that the food matrix has a substantial impact on the blood lipid response to SFAs. For example, SFA from butter increases TC/LDL, but SFA from cheese has a neutral or favorable effect on TC/LDL. Perhaps there is a layer of complexity there that attenuates the impact of SFA on TC/LDL in the context of a typical diet.

Hi Erik,

Thanks for the comment. If there is a clear and consistent long-term causal link between SFA consumption and serum cholesterol, it should be observable using an observational design (as long as the measurements are accurate, which admittedly is often not the case). The fact that there is variability from other factors (genetics, body fatness, etc) should not prevent the detection of an association, if you have a sufficiently large sample size. The reason is that noise does not eliminate an association-- it simply adds variability on top of it. That reduces the R2 value of the SFA-cholesterol link, but the absolute effect size of SFA consumption on circulating cholesterol, should not be affected. Likewise, the association should still be statistically significant in large sample sizes typical of most observational studies.

Regarding the argument that we don't see an association because our SFA intake is too homogeneous, I don't buy it. Observational studies generally report a SFA intake range of 2-3 fold in affluent countries (across quartiles or quintiles). If 2-3 fold differences in SFA intake have no impact on cholesterol, then why are public health authorities asking people to reduce their SFA intake by half?

If we cannot observe an association between SFA intake and cholesterol because the measurement is too noisy due to other impacts on cholesterol, that implies that observational studies are essentially useless for measuring any association between a dietary factor and a chronic health condition. Every chronic health condition is multi-factorial and there will therefore be substantial noise affecting any association, so doesn't your argument imply that observational studies are useless in general?

Regarding the stronger association in the vegetarian study you cited, I repeat that those types of studies are heavily confounded because vegetarians exhibit many differences in diet and lifestyle from omnivores. It is very difficult to attribute the difference to SFA intake per se.

Stephan:

"If we cannot observe an association between SFA intake and cholesterol because the measurement is too noisy due to other impacts on cholesterol, that implies that observational studies are essentially useless for measuring any association between a dietary factor and a chronic health condition."

Well, that was indeed part of Skeaff and Miller's analysis (Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2009):

"... the evidence from cohort studies of dietary intake of fats and CHD is mostly unreliable (with a few exceptions) because most studies have ignored the effects of measurement error and regression dilution bias."

I'm not saying observational studies by definition are useless, but I do assert that most of them so far have not been able to test the hypotheses about fats and CHD, because hardly anyone in the cohorts adhered to the recommended fat intakes.

So one has to regard the totality of the evidence. I consider Jakobsen et al's pooled analysis from 2009 as perhaps the best we have, although it too has its limitations.

Perhaps a 2-3 fold variation in SFA intake isn't a sufficient distribution. In the Seven Countries study, it ranged from 3 to 22 E% (a 7-fold difference), and SFA intake explained 89 % of the variance in serum cholesterol.

I'm sorry if this is beginning to look more like a discussion about fat than of meat.

Stephan, this "saturated fat-cholesterol" discrepancy between cohorts and randomized trials is indeed a bit puzzling. It's a bit surprising that this was not discussed in the context of Chowdhury's and Siri-Tarino's meta-analyses (if I remember right). I only became fully aware of it now.

You seem to accept that when saturated fat is replaced by PUFA, cholesterol is reduced (durably). But when SFA is replaced by carbs, MUFA or protein cholesterol reduction may not happen in the long run. Is that right interpretation?

As far as I know there is no formal meta-analysis on replacing saturated fat with protein. Dead end for protein?

Hooper et al. 2011 went through randomized reduced and modified fat trials lasting minimum 6 months. They show in the meta-analysis that when saturated fat is replaced with PUFA/MUFA ("modified fat) blood cholesterol reduction is 4 times higher (0,44 mmol/l) than when replaced with carbs (0,11 mmol/l, "reduced fat").

Replacing SFA with MUFA also has rather small effect as Clarke (1997) and Mensink (2003) have shown in their meta-analyses. Replacement of SFA by PUFA is by far the most efficaous "switch".

Perhaps this is a part of the explanation on top of what's been suggested by others?

Hi Erik,

I'm willing to consider the possibility that observational studies are unable to detect associations in high-variability situations, but that would be pretty depressing! Yet we know there are instances where observational measurements have been misleading. FFQ-based measures are certainly not very accurate for most food items, and we know that self-report of energy intake is quite inaccurate. Worse, misreporting differs by weight status, creating a very misleading bias. Also, studies often correct nutrient intakes based on total energy intake, which biases nutrient intake as well.

Also, measurement of blood lipids comes with a fair amount of variability. If I recall, TC and LDL can vary by as much as 20% from one day to the next.

All of that does make me skeptical of observational studies in general. Still, it seems remarkable to me that the SFA-TC association would be completely undetectable in most observational studies, given the strong relationship that is suggested by short-term RCTs. If that's true, then I would lose almost all confidence in diet-health observational studies.

I would be interested to learn more about regression dilution bias. I understand the general concept, but has anyone actually been able to test how large of an impact it has on the results of these studies, or is it still in the theoretical stage?

Hi Reijo,

You said "You seem to accept that when saturated fat is replaced by PUFA, cholesterol is reduced (durably). But when SFA is replaced by carbs, MUFA or protein cholesterol reduction may not happen in the long run. Is that right interpretation? "

Yes, essentially. I don't take a firm position on it (at least not anymore), but I do think the observational studies and certain longer-term RCTs raise interesting questions.

The explanation you propose makes a lot of sense. I need to read the references you cited, do some calculations, and think about it more.

This is why i read this blog, even though I'm not ancestral/Paleo, because you always have an open mind about science. I stopped reading all other ancestral/Paleo authors long ago, because they have a subjective, dogmatic belief in the miracle of meat and sat. fat, and cannot really take a dispassionate look at the data like you. Most of their 'arguments' are just juvenile ad hominem attacks, conspiracy theories about evil industries/corporations slandering meat, and the old standby: "real men eat meat". But you can go to a McDougall retreat, rub shoulders with vegans, and be inspired to take a second look at the data, so kudos to you :)

Now my two cents is this: since I'm not a trained scientist like you, I have to rely on my trusty common sense, and it tells me this: areas of the world where the consumption of animal products (protein and sat. fat) is low, like Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and large areas of the middle east and Africa, cardiovascular disease is very low, and so are certain types of cancer, and less consistently, diabetes and obesity. In parts of the world where where the consumption of animal products is high, the opposite is true. When people from the former go to the West and adopt the diet, they get fat, and they get the aforementioned diseases. You have to be delusional to not think this is insignificant. My conclusion matches yours: eat a lot of plant foods, with moderate to low animal products, favoring fish, poultry and eggs.

Here in Southern Appalachia, folks often add a bit of fatback or bacon to vegetables, then these veggies are a major part of a meal, along with a starch such as cornbread, sweet potatoes or winter squash. We still make our own bacon and hams, so have control over the curing mix used.

Which component(s) of cured meats appear to associate with increased risks? Any potential to make and enjoy a lower risk bacon?

My apologies, I made a mistake. The result of 0,11 mmol/l in Hooper's meta-analysis was about reduced *total* fat, not saturated fat. Thus, you can basically ignore my comment regarding Hooper's meta-analysis :)

1) I note a major discrepancy in the Blue Zone book when it comes to a description of the sardinian diet. In fact, the first guy the authors visit is found, covered in blood, inside a steer he is slaughtering (for the family, he says). Further, these centenarians grew up on LARD, not olive oil, which is a relatively recent shift. Hopefully the BZ book is closer to the truth for the other four groups described, but the Sardinian one is incredibly wrong. No conclusion can be drawn from that book.

2) The Tokelau study (discussed in the pages of this blog) shows clearly that heart disease and saturates are not correlated.

3) heart disease is nice, but it is overall mortality we are interested in.

4) I think no one disagrees that there is an optimal daily intake of flesh, probably around 1/2 lb a day (YMMV with latitude and seasons). It would be more interesting to find out if it is 1/2 lb or 1 lb.

I thought you made the argument in your previous blog postings that it is the nature of the LDL particles that matter and with a high saturated fat diet with low triglycerides, even though LDL is high, it won't be the bad kind of LDL, but the kind that is not dangerous. Sorry for the awkward summary, but I think you know what I am talking about. I would be grateful if you can clarify on this.

Hi Stephan,

Excellent post. Very thorough and well-referenced. However I do think focussing on one cause of mortality does distort the picture. Vegans and vegetarians tend to suffer from mental illnesses more often, probably due to a lack of certain nutrients.

I found your arg:lys ratio comment interesting, especially since I had never heard of it before! The methionine:glycine (or excitatory amino acids ratio to calming amino acids such as tryptophan to glycine, proline, serine).

Replacing some red meat with gelatin / skin / bone broths should balance these ratios out nicely (including the one you mentioned). It also helps reduce total iron load.

I just want to remark on the difference of 5-year risk of heart attack mortality among the populations of Eastern Finland and Western Finland. It was discussed on the blog-post of George Henderson

"The World's Longest-Running Refined Seed Oil Experiment"

https://www.blogger.com/comment.g?blogID=8550919611653842066&postID=2342126671558795904

than the people who live in the East Finland belong to the Orthodox church and may consume more omega-6 polyunsaturated oils due to their religious requirement to abstain from animal products during numerous lent periods.

The lent oil for the Orthodox Christians and Catholics who live in a warm climate is olive oil, but in the cold climate regions seed oils are used during lent periods.

If modern studies demonstrate that there is no real reason to believe that saturated fat intake is associated with cardio disease, why on earth do organizations such as Harvard still promote such a low sat fat, high grain, seed oil type diet? This baffles me to no end. Are they hanging on to old beliefs? are they really industry shills as many Paleos would make us believe?

Hi Giantess,

There is still controversy around the question of whether or not SFA contributes meaningfully to heart disease. Reasonable people could come to different conclusions based on the evidence. I don't think you have to be an industry shill to believe SFA is harmful, and I don't think most of the people advising us to limit SFA intake are shills.

Excellent post Stephan!

Are you going to change anything in "the ideal weight program" based on the research you did here? I really like the program and from what I understand it is created to both obtain a suitable weight and staying healthy in general (lean maintainance diet). But based on your research here so maybe a smaller meat intake with more focus on legumes would be better for your health?

@TheGiantess

Well, there's also systemic inertia when it comes to bureaucratic stuff. It took a long time to get the anti sat-fat dogma to be "a given" in the mind of the layman, and I presume it will take a long time to shift the mindset the other way. And I think, for 2/3 of the world population, all these considerations go way past their attention. I'd rather say that 2/3 of people world-wide only think about getting something to eat that they can survive on, no matter what their nutrients.

Hi Stephan,

I've been thinking about some evidence linking the intakes of glycine and methionine to the inflammatory status of animals.

In this article, you mention the arginine:lysine ratio, but some other animal studies also show that increase glycine intake or decreased methionine intake might have beneficial effects on health. In some studies, glycine has even reversed metabolic syndrome in rats.

http://180degreehealth.com/amino-acids-metabolic-syndrome/

Plant proteins (eg. potatoes, soy) also have a good glycine:methionine ratio. It could be that some of the "harmful" effects of animal protein is caused by the low ratio of glycine to methionine.

Hi Michael,

Glad you like the Ideal Weight Program. We don't have any immediate plans to change it. Since body fatness and energy balance are important determinants of cardiovascular health, weight loss will tend to reduce risk. Maintaining the loss over time is equally important. The key is to have an intervention that actually works. We also believe that the foods we include add up to a healthy overall dietary pattern.

We do offer a variety of potential protein sources to give people flexibility in how they apply the IWP guidelines. For people with cardiovascular concerns, it might make more sense to focus on the beans, fish, and poultry sources rather than other sources of protein. It's also possible to follow the diet as a vegetarian.

We can't make specific claims about the impact of the IWP on disease risk. However, within the IWP framework, we provide enough flexibility to allow people to pursue health and environmental sub-goals.

STEPHAN!

This is like having "the old Stephan" back, by which I mean just your way of addressing stuff that I liked so way back when you blogged about primitive populations and such.

Good work. For real "Fair and Balanced," not the Faux News version.

Just an anecdote so salt grains in play, and also, if cholesterol numbers are important to anyone. After a few months of a diet change where I reduced protein portions to modest (8oz ribeye instead of the pound, etc.), upping substantially my intake of beans and potatoes, and cutting out most forms of ADDED fat. IOW, no fear of any natural fat, but tend towards eating it in its whole food source. I actually like salads more with just small dribbles of EVOO, for instance.

So, just had blood work and Total went from 220 to 180. LDL, from just over 100 to about 70, HDL from 120s to 90, and Trigs from 30s to 80s. I consider that increase in Trigs to be a good thing.

Anyway, the way you're treating this is to me like back when I read John Lott's book about crime in places where it's easy to get concealed carry permits. He titled it "More Guns Less Crime" but to me, it should have been titled "More or Less Guns, More or Less Crime."

Excellent. Can't wait to read the next two installments.

Hi Stephan, It's been a while since I read your blog, just doing catch up. This is very good series, thank you!

I've been looking at the composition of different vegan diets lately and wonder how much this confounds the research, even if we were only looking at 'healthfood shopping vegans'. In particular, some vegans on a budget seem to use a lot of omega 6 oils in cooking (organic, non-GMO of course!), and some eat a lot of refined carbohydrates (pasta and bread, particularly) and surprisingly few vegetables. Some eat virtually no omega 3. Within veganism, I've found very healthy and very unhealthy people, possibly the healthiest and unhealthiest that I've met in my career.

Another factor which may come into play with Ornish's and Esselstyn's diets is the increase of vegetable intake -- independent of protein. The Wahls Protocol, for example, advocates the kind of vegetable intake one achieves on Ornish but advocates keeping not only lean meat but organ meats and animal fats. Her work is to maximize the intake of brain-protective nutrients through food, and not cardiology, but it suggests another research question.

I just noticed that of the five citations following your statement "it appears relatively clear that the China Study does not support the conclusion that meat consumption is associated with cardiovascular disease or cancer risk," two of them are links to Campbell's papers supporting those claims. Did you mean to link to something else instead? (PS - this doesn't need to be posted as a public comment; just using it to get in touch).

Hi Michael,

I deliberately linked to Campbell's citations out of fairness. I want anyone to be able to evaluate my statements by hearing both sides of the story. My view of Campbell's papers is that they do not support his claims, for the reasons outlined in the other sources I linked to.

There are several problems with his claims, but this is the primary one. Campbell reported indirect associations (A -> B -> C) when direct associations (A -> C) were available. The direct associations, which any qualified statistician or epidemiologist would have focused on, do not support his claims. I'll leave it to others to decide why he analyzed the data in this way.

Post a Comment