In 2000, the International Journal of Obesity published a nice review article of low-fat diet trials. It included data from 16 controlled trials lasting from 2-12 months and enrolling 1,910 participants (1). What sets this review apart is it only covered studies that did not include instructions to restrict calorie intake (ad libitum diets). On average, low-fat dieters reduced their fat intake from 37.7 to 27.5 percent of calories. Here's what they found:

Low-fat intervention groups showed a greater weight loss than control groups (3.2 kg, 95% confidence interval 1.9-4.5 kg; P < 0.0001), and a greater reduction in energy intake (1,138 kJ/day, 95% confidence interval 564-1,712 kJ/day, P = 0.002). Having a body weight 10 kg higher than the average pre-treatment body weight was associated with a 2.6 +/- 0.8 kg (P = 0.011) greater difference in weight loss.In other words, low-fat groups reduced their calorie intake by an average of 271 calories per day, and lost 7.5 pounds (3.2 kg). When they considered only people who started off overweight, they lost 12.8 pounds (5.8 kg). The investigators noted that the results were similar no matter what the duration of the trial, because weight loss plateaued fairly quickly. This is all without any instruction to reduce calorie intake, therefore we can assume these dieters were eating to fullness. The investigators concluded:

A reduction in dietary fat without intentional restriction of energy intake causes weight loss, which is more substantial in heavier subjects.Their conclusion was modest compared to certain other low-fat diet trials, which stated outright that eating fat leads to obesity. Their findings mirrored those of a longer trial that lasted two years (2).

Low-Carbohydrate Diets

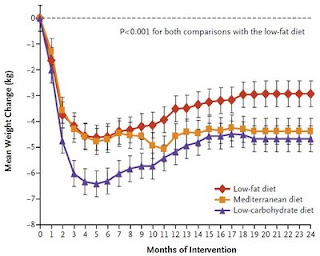

The best low-carbohydrate diet study I've seen was published in 2008 in the New England Journal of Medicine (3). 322 "moderately obese" participants were placed on a low-carbohydrate diet, a calorie-restricted low-fat diet, or a Mediterranean diet, for two years. The low-carbohydrate group's carbohydrate intake decreased by 130 grams per day, which is about half of a typical person's total intake, and neatly corresponds to the reduction in calories of 561 per day, despite not being instructed to reduce calorie intake.

At two years, the low-carbohydrate group had lost 10.4 lbs (4.7 kg), which is similar to the average weight loss seen in long-term low-fat diet trials that do not impose calorie restriction. At that point, they had been relatively weight stable for nearly a year. Markers of metabolic health improved, and total and LDL cholesterol decreased.

Which Macronutrient Causes Obesity?

Trick question! Overall, these studies show that both fat and carbohydrate can be fattening, and each can also be slimming-- it just depends on the context. Food reward is the concept that makes sense of these seemingly contradictory findings, as fat and carbohydrate are both major reward factors. Reducing one or the other appears to decrease the body fat setpoint, leading to reduced hunger and a new lower weight plateau. This plateau effect is remarkable in all the diet groups of the low-carb study mentioned above (4):

If food reward causes obesity, then diets that are restricted in other ways should also cause weight loss...

Vegan Diets

In 2002, the journal Obesity published a paper on the long-term results of a diet trial comparing a vegan diet to the standard "heart-friendly" low-fat, low-cholesterol NCEP diet in overweight women (5). After one year, vegan dieters had lost 10.8 lbs (4.9 kg), although after two years, the loss had diminished to 6.8 lb (3.1 kg). The vegan diet outperformed the NCEP diet in terms of weight loss, although to be fair, I don't think the NCEP diet is really designed to be a weight loss diet.

A separate 74-week vegan diet trial in diabetics came to a similar conclusion, and also showed that the vegan diet improved metabolic function somewhat (6). In fact, markers of metabolic function improved in all the weight loss diets I mentioned in this post, suggesting that energy balance is a critical factor in metabolic health. I believe that garden-variety insulin resistance is probably mostly due to energy imbalance, i.e. energy intake exceeding what the body can constructively handle. It starts off as a reversible phenomenon but can become semi-permanent over time. I also suspect that long-term energy imbalance plays a role in elevated blood cholesterol and other factors leading to heart attacks.

Paleolithic Diets

For those who aren't familiar, "paleo" diets only allow categories of foods that were available before the advent of agriculture. That means no processed foods, no grains, no beans, no refined sugar, no dairy. Paleo diets are mostly composed of some combination of meat/organs, seafood, starchy tubers/roots, vegetables, nuts, fruit and eggs.

Unfortunately, the paleo diet trials published to date lasted no longer than 12 weeks. However, Dr. Staffan Lindeberg's group showed that 12 weeks of a paleo diet caused a substantial decrease in calorie intake, a weight loss of 11 lbs (5 kg), and a remarkable improvement in metabolic function in overweight patients with diabetes and pre-diabetes (7).

Again, participants were not instructed to reduce calorie intake. Yet, a separate analysis of the data showed that according to questionnaires, they felt just as full as the comparison group that ate 31 percent more calories on a Mediterranean diet (8).

One of the things I like about the paleo diet is it reduces food reward (especially industrially processed items) and other potentially problematic foods, while remaining highly nourishing and not necessarily imposing limits on macronutrients.

Putting it All Together

So here we have four diets that are diametrically opposed to one another. On one hand, we have low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets, and on the other, we have vegan vs. high-meat diets. All four cause a spontaneous decrease in calorie intake in overweight people, all four cause fat loss, and all four improve metabolic markers in overweight people with diabetes risk factors. I feel that food reward provides a compelling explanation for the evidence as a whole. Reduce the rewarding quality of the diet, and you get changes that are consistent with a lowered body fat setpoint. I think once we take a broad view through the lens of food reward (while not forgetting other potential mechanisms), we can start designing fat loss strategies that are highly effective because they're based on a deeper understanding of the underlying principles involved.

141 comments:

As ever a fascinating post, Stephan. I've been low-carb [mostly] for four years but I seem to have lost my way recently and put some weight back on.

I sense it's time for a change in order to kick-start my weight-loss again as I'm too dependent on certain foods such as cream.

Thanks for the useful information.

For those who aren't familiar, "paleo" diets only allow categories of foods that were not available before the advent of agriculture.

You should loose the 'not' in that sentence :-D

What about the junk food diet as that one professor was conducting a short time ago (he lost weight on it)? Aubrey de Grey also lives mostly off junk food and is super slender...

Megan

I love cream but find I need to cut it out or reduce it if I want to lose fat. It is too easy to drink down hundreds of calories in one go.

@David: If you're talking about the twinkie diet, Stephan wrote a great article here (http://wholehealthsource.blogspot.com/2010/11/twinkie-diet-for-fat-loss.html). It's not really relevant to this, because it involves forced calorie restriction.

Thanks for the info,I know some people who are sensitive to carbs, a plate of rice today and a flab in the waist tomorrow, I just haven't yet analyze my diet to see what's making my weight hiking up.

Great series, Stephan.

I'm all with you with the whole foods thing. Nothing broken...sure, eat any macronutrient ratio you want (just avoid those NADs). No problem. Simple stuff. Metabolically dented/damaged, well, that's not so simple.

I'm curious, how does your take on food reward differ from Robert Lustig's? He's been writing about this for well over 5 years and has some proposed mechanisms, so the idea is not that new. But I'd like your take on it since his is a bit more insulin-centric than yours.

This sounds similar to the thinking behind Seth Robert's diet (Shangri-La). There's little food reward in light olive oil.

I feel that food reward provides a compelling explanation for the evidence as a whole.

All these diets force people off industrial food one way or another (at least they used to, these days industry produces more and more food for all types of dieters).

Don't theories that something about industrial food (trans fat, omega 6 overload, phytoestrogens etc. etc.) is directly harmful fit the data just as well?

What's the easiest way to differentiate between the two?

What do you mean by "rewarding quality"? It seems to me that different diets don't necessarily reduce the overall rewarding quality of food, but they reduce the diversity of distinct food rewards. Low carbohydrate diets reduce the starch & sugar reward, whereas vegan diets reduce the meatiness reward. The bland liquid food diet from part II reduces nearly all food reward.

Perhaps the success of a diet depends on how many food rewards it restricts, as the body fat set point is adjusted upwards a certain amount -- not necessarily uniform across rewards -- by an abundance of each type of reward. If this is true, a diet that restricts only a subset of the rewards another diet restricts shouldn't perform as well. This would explain why all restrictive diets perform better than the standard diet, as the standard diet is abundant in all food rewards.

So it would seem that a plateau period is actually a marker of success rather than the failure many see it as. The setpoint has adjusted. That's no bad thing.

But it does logically lead to the problem of a restrictive diet to loose weight, then rebound after the diet is "over".

Nice series so far Stephan. I am curious on what your take on Tim Ferris' slow carb diet is. Sure, it reduces reward and increases protein and fiber (both leading to increased satiety) . . . except on the off day. Could you elaborate on why you think the off day is beneficial?

Do you know if the low-fat and vegan diets in these studies allowed sugar (and other caloric sweeteners)? I find sugar to be the most rewarding "food", though it is more rewarding when mixed with fat. And I wonder if that is something that all 4 diets have in common (restricting sugar).

Personally I have tried a few of these diets and lost the most weight when I was vegan with no sugar. However I found the diet VERY difficult to maintain and after doing some research I became concerned about the lack of nutrition in the diet (ie lack of B12, etc.).

Hi Stephan, I've really been enjoying your food reward series. It's making me take a hard look at some of the "paleo-approved" foods that I may overindulge in (such as almond butter). Also, I can't wait to hear your interview on the 24th, especially the answer to the question of "What Stephan Eats". I confess that the recent brou-ha-ha on Don's blog regarding saturated fats has me back to being a little baffled about what I should be eating. I hope that a description of your eating habits will resolve some of that confusion. Thanks!

Hm, doesn't this imply that we can drink a shot of refined corn oil every day, not feel hungry (and hence lose weight), and still get a fatty liver and who knows how much bodywide inflammation? Can we simply ingest tasteless poisons from now and get skinny?

This theory, while compelling, may initiate some dangerous actions on the part of people trying to lose short-term fat at the expense of long-term health, without knowing the full picture of what real health is. I like how it explains weight plateaus in many people though. A bland VLC diet could indeed be the quickest way to "ripped-ville".

Can we also please get a definitive answer Stephan as to why you think fasting insulin does not contribute to obesity and/or weight loss? Do all of us burn the same amount of fat between meals? Isn't access to fat stores a major factor in being lean?

And I also agree with PoisonGuy that this also doesn't address the metabolic problems of those who are "broken" or with outright diabetes. Is simply eating bland food the answer to their problems?

I wish there were a study on those with already damaged metabolisms where they were forced to eat dry boiled potatoes. Would they be "cured"? Can they all of the sudden handle carbs because they're tasteless?

@ gunther gatherer

Good point. It is important to remember that while losing weight is important in regaining health, there are a lot other factors. For example, it is possible to display metabolic syndrome without being overweight, i.e. hypertension, insulin resistance, etc. Simply losing weight will probably not completely resolve those issues.

Reducing food reward generally increases satisfaction. In this sense, what was once bland, actually becomes delicious. Right?

I think Stephan would agree that the weight loss in all the diet groups occurs because the subjects are now burning body fat (hence they are no longer hungry). How do we explain this? What started them using their body fat all of the sudden if not because fasting insulin went down?

And if we agree on that premise, what caused it to go lower: simply the TASTE of the food? I thought weight loss was more about what happens between meals as opposed to during the meal itself.

I can entertain the idea that maybe intense flavour enhances the insulin spike, but stinkbugs are delicious to a Kitavan while disgusting to us. Wouldn't it still be rewarding to him though? I saw a documentary where the camera crew offered raisins to some Kombai tribesmen and they spit it out in disgust.

Doesn't a food's "reward" simply depend on what you've grown up eating?

What is the evolutionary explanation of food reward? Biological theories without an evolutionary component are at best incomplete.

Why does the set point not compensate by increasing the metabolism/decreasing hunger? Is it because we are expected to eat 3 square meals a day (plus snacks)? Does intermittent fasting/reduced meals counteract food reward?

This "setpoint" explanation is weak, because anything can be explained by it. It means nothing. Unless you put forward a THEORY of HOW setpoints work at the molecular level, and back it up with evidence, then ANYTHING that cannot be reconciled in the data, can be explained by setpoints.

I think you are having problems with coming to terms with heterogeneity: people respond differently to food/insuline/inflamation/etc... some people's systems are quick to adapt but others do not. Then, you have decide who to target with your work...

"This is all without any instruction to reduce calorie intake, therefore we can assume these dieters were eating to fullness."

Can we really assume this? It's hard to do a blind trial with diets. The participants usually know they're in an experiment, so that may affect their behaviours.

To follow up on drjill's comment, I’ve heard Taubes say that low fat diets almost always end up being a low carb diet as well because fat and carbs are so often packaged together in the SAD. People are instructed to eat a low fat diet so they pass on the chocolate cake because it has too much "fat". But in reality they have just greatly reduced their carb/refined sugar intake as well.

Was there a comparison of the CHO (especially sugar) intake in the low fat dieters?

I already posted a comment but I think the internet ate it - so sorry if this is duplicated.

I think this explanation fits well in an evolutionary perspective. Humans have occupied a huge variety of environments providing vastly different average diets wrt macronutrients. If humans could not fatten on all of them, we would not see persistent groups of humans in all of them - but we do. In the past, we HAD to be able to store excess food from time to time. It makes sense that "food reward" can come from anything but that combinations of macronutrients do it best - and perhaps our ancient biochemistry, left over from our days of arboreal foraging ensured that we possibly favour a combination of carbohydrates and fat (maggot-infested overripe fruit, anyone?), but that anything will do AND - this is important - that the mechanism is tied to culture as far as identifying foods that are and will continue to be available and non-poisonous for the given environment. So if you're an Inuit, you are probably culturally conditioned to be able to eat an excess of extremely palatable food FOR YOU (mmmm seal blubber) but if you're a !Kung San, you'd be better able to scarf porcupine with a side of tubers. As a highly mobile, highly adaptable species, it doesn't make sense that there would be one particular macronutrient or combination thereof that would induce fat storage. We ought to be able to pile on the fat with anything, but it MAY be easier, if we evolved from arboreal, fruit & nut eating primates, to do so with carbs & fat.

As far as the concept of a set-point goes... that one's a little tricker to explain from an evolutionary rationale, and I am running out of internet time...

Re an evolutionary explanation of food reward, this video series (there are 6 total, just linked to the first; HT Matt Stone) on porn addiction uses food frequently as illustrative.

It makes an interesting theory about reward being used to override satiety for both food and sex. So in the former case, reward gets you to chow down to store up calories.

The series also points out that it is not the one-time ingestion of something that is problematic. Instead, it's the repetitive habit (and resulting dopamine signaling issues) that creates the phenomenon of needing to do something more frequently, but liking it less.

BTW, I think it's a mistake to equate reward and taste (which I was making initially). Taste is likely a part of it, but there are probably others too. Perhaps the reason that both LF and LC diets do well is not that they are tasteless, but that they both tend to remove highly processed foods that are laden with sugar, salt, and veggie oils that over-stimulate the reward system.

I find it ironic that you use the NEJM study as an example to explain your theory. As that study clearly showed that restricting carbohydrates led to better fat loss in a direct comparison to low-fat and Mediterranean diets.

In addition, people on low-fat calorie restricted diets don't just restrict fat they also intuitively restrict simple sugars as well which probably explains there modest weight loss.

Hi Ulla,

Thanks, I'll fix it.

Hi David,

See the response by engineering-health below.

Hi Poisonguy,

I'm not familiar with Dr. Lustig's ideas but perhaps I should look them up.

Hi Taw,

That could be part of the explanation, particularly for the paleo diet. It's tough to separate the two completely in humans, but in animal models you can accelerate obesity by increasing the diet's reward value in a way that's tough to explain by changes in nutrients.

Hi Theo,

I'm not familiar.

Hi Gunther,

Yes, I do think you can get thin eating nothing but tasteless refined industrial foods, but I wouldn't recommend it. Being in energy balance will help people with a "broken" metabolism, to a degree that depends on the extent and duration of the damage.

I think decreased fasting insulin occurs as a result of weight loss and negative energy balance, rather than as a cause.

Hi Avishek,

I certainly hope so, but that's not totally clear to me at this point.

[Whoa, looks like my comment got eaten too. Let's try again!]

Re an evolutionary explanation of food reward, this video series* (there are 6 total, just linked to the first; HT Matt Stone) on porn addiction uses food frequently as illustrative.

It makes an interesting theory about reward being used to override satiety for both food and sex. So in the former case, reward gets you to chow down to store up calories.

The series also points out that it is not the one-time ingestion of something that is problematic. Instead, it's the repetitive habit (and resulting dopamine signaling issues) that creates the phenomenon of needing to do something more frequently, but liking it less.

BTW, I think it's a mistake to equate reward and taste. Taste is likely a part of it, but there are probably other factors too. Perhaps the reason that both LF and LC diets do well is not that they are tasteless, but that they both tend to remove highly processed foods that are laden with sugar, salt, and veggie oils that over-stimulate the reward system.

* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKDFsLi2oBk

Hi Greg,

My hypothesis is that the homeostatic mechanism doesn't react because highly rewarding foods increase the setpoint.

Hi ett094,

That's not how science works. If you can demonstrate an effect, it exists whether or not there's a molecular mechanism behind it. That being said, a lot of the mechanism has been worked out. If you're interested, there are several nice review papers on the matter such as "Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight".

I think heterogeneity is part of the equation, but if we were seeing true statistically distributed heterogeneity, average weight changes would be zero in those studies because some people would lose, some would gain. There will always be heterogeneity in human diet studies, due to adherence etc., but that does not imply that a theory is unsupported. Keep in mind we're all the same species. Lions didn't evolve to eat eucalyptus and koalas didn't evolve to eat meat.

Hi GK,

It's a potential confound, but I doubt people are going to starve themselves for two years without being asked to...

Hi Todd,

I disagree with Taubes on that. In the low-fat studies, if carbs decreased at all it was a very modest difference. In some, carbs increased.

Hi Jason,

Why use the low-fat diet group in the NEJM study when I can use much better data from a meta-analysis of many low-fat studies?

Stephan, you write "highly rewarding foods increase the setpoint"

Do they increase a "setpoint"? Or do they increase eating via appetite stimulation which results in a higher fat mass?

Not sure if this is semantics or a point I'm not grokking.

Stephan; really NOT enjoying this series. You keep us in suspense too long!

General rule: in a place of food scarcity, the ability to get fat is a bonus. It is just in a modern era where we have cheap and plentiful food that it becomes a problem.

Regarding heterogeneity, when you do a study with modern Americans there are no "lean" people there. Take as a basline a BMI of 20 for men. What is that -- less than 1% of the population? But a 20 BMI is probably what our "normal" weight was for 100,000 years.

Hi Stephan and thanks for your reply.

"I think decreased fasting insulin occurs as a result of weight loss and negative energy balance, rather than as a cause."

This is rocking my tiny VLC mind. Can you please explain it? I mean, how do we reduce calories if fasting insulin is high? We would be hungry and not able to access fat stores, hence the diet would fail due to bingeing.

In your opinion, what comes first: lowered calorie consumption or lowered hunger/adipose tissue access??

gunther gatherer -

Frequently on this and other blogs, commenters (and sometimes the author, but not Stephan) suggest ways that diabetes can be "fixed" through diet. I'm not saying you've done this, but in response to your question as to whether bland foods are the answer to a diabetic's problems, my take is that there is no simple answer.

Type II diabetes is not primarily the result of wrong diet or overweight and sometimes not at all. (Most people who are obese do not develop diabetes, while many people who are not obese do.) See Jenny Ruhl's comment, on Stephan's previous post, about the metabolically damaging effects of modern toxins. In addition, a variety of genetic and epigenetic factors are at play.

Diet and fat loss can help control blood sugars, and may be able to halt the march from pre-diabetes to diabetes, but they can't solve these underlying problems.

"Roughly 20% of the people with Type 2 diabetes are thin, and 75% of obese people never get it."

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124269507804132831.html

@gunther gatherer -

"And I also agree with PoisonGuy that this also doesn't address the metabolic problems of those who are "broken" or with outright diabetes. Is simply eating bland food the answer to their problems?"

I don't know if it's been the subject of controlled studies, but the McDougall diet (very low fat starch-based vegan -- darn near bland in my opinion) has had quite a bit of success treating T2 diabetics. Carbs average around 80% of the diet and fat is limited to what's found naturally in grains, tubers, and vegetables (about 7 - 12% of total calories). Not a far cry from the dry boiled potatoes scenario you mentioned.

Stephan:

Please consider adding a "food reward" label to your blog so that readers can review these entries easily.

"Being in energy balance will help people with a "broken" metabolism, to a degree that depends on the extent and duration of the damage. "

Nice post Stephan, but now I am really worried...does this mean that since i have been obese since childhood i have no hope of repairing my metabolism? I have lost almost 60 pounds in the past. But now even though I have been strict paleo for almost 4 years now, and i can't seem to be able to lose weight. Am i broken without hope? How do you measure damage severity?

Can you please give us examples of things that we can measure that your theory does NOT explain? in other words, can you give us a hypothetical human being whose behavior can be evidence against your set point theory (would you need a brain scanner, or would you need to base it on them telling you whether they like their food?.....)

I don't understand this paleo and genetical dieting...

I mean, we now know that epigenetic inheritance influence our ability to utilize nutrients and its configuration is changed with single generation (even with single event) and passed to next ones (with diminishing returns if environmental signal is removed from the environment).

This mean two things - what was happening 10000 years ago probably diminished by now along with the adaptations in multiple domains of our genetic configuration so what happened back then is of little or no relevance to our current environment and genetics (the exact influence needs to be quantified thou for better understanding). Second, we adapt to our current environment quickly and we are probably able or will be able soon to deal with environmental changes that affect our input.

This makes me think that success of those diets is probably of psychological nature and not entirely related to food rewards (good point by Ganther) system. Its effect might represent some part of the equation while other might be that people who do specific diet tend to be more aware of what they eat so they eat less. There are anecdotal evidence that even if you simply log your weight every day you will lose weight for the very same reason without any consciousness thought.

You probably evolved to function the best in environment of your near ancestors (and it seems 'near' can really be matter of very short space-time distances). The signals are different in other environments even in the same time (even something as transparent as microbiota - there is research pointing out that microbiota profile change with obesity for instance). We try to mimic the real world in a lab as good as we can, but this is something that simply can not be artificially recreated in this moment of time, and there is big possibility that it will never be, so solution will probably be available via different paradigm.

"http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21118562"

"or a Mediterranean-like diet (n = 15) based on whole grains, low-fat dairy products, vegetables, fruit, fish, and oils and margarines during 12 weeks" I don't know how rewarding such a diet would be. Specially compared to a diet of so called junk-food. Do you have more data of that diet? I wonder if food reward can explain most of the difference between that diet and the paleo one, unless factors like opioids or other things in grains and diary had an influence. What's your opinion?

Hi ett094,

Here are a few examples of observations that would not be consistent with the hypothesis:

1) If people/animals held on to their excess fat mass after short-term overfeeding, rather than losing it

2) If people/animals stayed lean after calorie restriction, rather than gaining the weight back

3) If eating bland food through a tube ad libitum did not lead to fat loss in the obese

4) If eating bland food through a tube ad libitum led to a similar decrease in calorie intake in lean and obese people

5) If low-fat diets caused decreased calorie intake and fat loss, but low-carb diets caused increased calorie intake and fat gain, or vice versa

6) If the cafeteria diet did not cause more calorie intake and fat gain in rats than a pellet diet of similar nutrient composition

7) If surgically removing fat from rats or humans did not result in a return to the same fat mass as a matched non-operated control group

8) If lesions to hypothalamic structures, or alterations in neuronal signaling mechanisms in the hypothalamus, did not lead to a change in the defended level of fat mass

A short list of possible observations that would cast doubt on the hypothesis. I think that will do for now...

Since I was 12 years old, carbs have been oatmeal, sprouted grain bread, sweet potatoes, potatoes, rice, and fruit. Fats have been nuts, dairy, small amounts of olive oil, small amounts of coconut oil, and fish and meat. I have maybe eaten processed foods a couple dozen times since then (I am 21). I never intentionally add salt to my foods, and actually prefer them prepared in a very simple fashion. My body fat has never been above 8%. I can eat A LOT of food, and still will not accumulate body fat. I can gain weight, but it is all muscle. On an average day, I am around 6% bodyfat and in great health. I can run for hours on end if you want me to, and I can lift moderately heavy weights for many repetitions.

This is not to brag. This is just to say that food reward definitely plays a part in bodyfat setpoint. I believe I have a low bodyfat setpoint because my food reward is low...but i do enjoy and savor all of my meals! Also, I have eaten high carbs, low carbs, high fat, low fat, high protein, etc. Macros change all of the time depending on how I am feeling in a particular day.

Steven, I think you are way ahead of the crowd on this idea about food reward. It seems to make a lot of sense out of things for me (like why I can eat so many calories and still not "get fat" or flabby or anything. It all just goes to the right places). haha.

Thank you so much for your research. It is top drawer in my book.

NRH

I would really enjoy a lively debate on a podcast between Stephan and Gary Taubes, Ron Rosedale or Peter from the Hyperlipid.

Is it possible the four diet trials succeeded due to the Hawthorne effect?

I am getting the feeling, as I try to understand the various findings and views here on Food Reward, that the consistent element in weight loss is a reduction in grain carbohydrates, and a severe reduction in sugar and vegetable oils (“PUFA”) compared to the normal Western diet..

You can eat just about anything, apparently, and lose weight, probably settling on a different weight with the various different diets, but what you cannot do is eat the typical American or junk food diet of chips and candy bars (low saturated fat and high sugar) and expect to lose weight.

Personally, I have been on a PaNu type Paleo diet for about a year and I am down about 10 lbs., which is not bad considering I was not overweight when I started. My tennis coach tells me I look like a UFC MMA fighter, which ok with me, so long as I avoid the damaged ears. The way to lose weight on that diet, as I see it, is to avoid rice and grain carbs, and sugar and PUFA, of course.

As I see it, what your body is sensing, on that PaNu diet, is that there is plenty of rich and fatty food available, so there is no need to store fat. If you need fat you can eat it.

Conversely, in a diet rich in carbs, your body senses that fats from the environment are in short supply and the body stores more fat. And the whole process goes crazy when you eat too much sugar and PUFA. You can eat some sugar, from fruit, or even sugar cane, but sweetened foods and fruit juices are disaster.

I had a plate of curried potatoes a few days ago: it was delicious, but is the excellent taste going to make me fat? It was very rewarding…

Consider also about what is missing from the typical low fat and low organ meat diet: choline.

And I should mention that I am 66.

Ok, so...

What's food reward?

Is it multi-path? What are the pathways?

I cannae take the cognitive dissonance! okay, maybe I can, but it hurts to stretch my thinking. 2 questions

a) you've talked before about inflammation from omega-6 imbalance being part of the cause of obesity (inflammation in the...hypothalamus??..messing up leptin system) - do you still believe that, how do you see omega 6 and obesity

b) how does this idea fit with the idea that the 'diseases of civilzation' all have a common cause - do they all arrive together due to food reward only, or do refined carbs/sugar, gluten grains and maybe omega 6 also fit in?

Denise,

Please provide the evidence supporting the McDougall diet. I'll take a stab at the "success" stories. ppl eating whatever they wanted, stopped eating whatever they wanted for a short amount of time (<1 year) and lost weight.

It would help for me to have "food reward" defined, as well. For instance, I find many of the foods and combinations of foods on an ancestral diet, which is quite low carb, though typically not VLC, very rewarding.I have been able to happily eat this way since the latter months of 1999 - originally started as a "clean" eating low carber, precisely because my food tastes "good" and because of excellent "satiety" - but as I define that. I am not sure of how you are defining "food reward" and "satiety." My impression is that your definition of "reward" is coming from the totally different almost addictive qualities of highly processed foods. Am I on the right track?

Hi again Stephan. I'm still very curious about your fasting insulin statement. If this is the case, by what mechanism does a VLC diet work then?

Is it just because we take out carbs and it all gets boring, so it lowers appetite?

I think a tighter definition of reward would be useful.

In my self experimentation and forced overfeeding of 5000 calories of delicious fat and protein caused weight loss, even while consuming chocolate (it was 70 - 91% from Theo's) and red wine.

I don't find calories to be a significant variable in weight loss. I can even do one or two day binges on high reward food and snap back pretty quickly to my new "lower" set point.

Finally, I would like to point out one contradictory data point to your theory. While consumption of most artificial sweeteners seems to cause weight gain (and can even cause cephalic insulin responses FWIW) in agreement with your theory about food reward, there are several potent artificial sweeteners that do not have this effect (ex. Xylitol and Stevia). In fact, those two in particular seem to have some beneficial effects on health and body fat regulation.

A few drops of Stevia is about as sweet as a cup of sugar. If you can feed rats stevia soaked pellets and they don't gain weight you might have to go back to the drawing board. Of course, Stevia is reputed to have an "acquired" taste, which is not present in the purified form (Truvia, ty coca cola) and would make an excellent control.

Thus if you feed rats Truvia and normal Stevia extract in equivalent concentrations and keep all other variables the same, your Truvia rats should get fat.

-The GeekBeast

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20393989

Mice fed Stevia did not gain weight, Mice fed sugar got fat.

All variables being the same there is something about stevia vs sucrose that is either affecting the reward value of the food (in these specific mice) or the correlation between food reward and weight loss might not be causal.

Here's to hoping for some rat study comparing stevia, xylitol, and sucrose consumption in rats vs a control.

-The GeekBeast

Seems unlikely food reward is just about taste. The sucrose mice probably got a nice opioid reinforcement that the stevia mice didn't.

@Matthew: There is a ton of literature on stevia being both an insulin stimulator and sensitizer.

Here's one study comparing preloads of sucrose, stevia and aspartame: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2900484/pdf/nihms187942.pdf

The sucrose preload contained about 200 cal more that was not compensated for. Indeed on the whole the sucrose group consumed 300 cal/day more than the other groups. Seems we don't sense sugar calories well?

Interestingly this study showed stevia lowered insulin levels and glucose levels which is in contrast to a lot of the literature on stevia.

How this works with the food reward?

Stevia tastes like some bad chemo too me. After prolonged usage I kinda like it more, but it still sux compared to other sweeteners.

The problem with food rewards are that they change - i.e. acquired taste, like that with Stevia.

This research confirms that:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/307/5716/1776.short

So, is the main motive that some foods are rewarding by default, that is, brain doesn't need to analyse food content and will produce rewarding chemicals when such foods are consumed because that is implanted in genetic code or something ?

Interestingly enough, my baby girl which doesn't like sugary foods at all will drink Vitamin C water if I add Stevia to it (2g VC, 200 ml water, 1 drop of liquid Stevia), otherwise she wont touch it. For her, its definitely rewarding more then any XYZose.

There seems to be a good reason to suspect that food reward plays a role in energy intake. I don't know if I would go and call it the TOE, though. Why are you calling it the "dominant factor" rather than another piece of the puzzle? Yes it does appear that if you eat bland food you can eat less and if you eat less you can lose some weight, but there is nothing in any of these posts that dismisses the leptin resistance theory of obesity or makes food reward out to be more important. Bland tube food could have restored metabolic health not only by reducing fat mass but by reducing inflammation and circulating insulin. All of the rat studies could have caused leptin resistance which could enable food addiction in the first place, in fact there are plenty of studies that show that on isocaloric diets the difference in amount of linoleic acid makes a profound difference in the amount of fat they accumulate.

What of the phenomenon of 20 year olds eating nothing but hyper-palatable junk food and staying lean until their 30s? They could have no developed a food addiction yet but they could have also not developed metabolic syndrome yet. And what of people on diets that address health first that lose upward of 100 pounds in a year rather than these paltry amounts in the studies? Those people who seemed to lose quite a bit of weight on a multivitamin?

And as for insulin resistance, what is the reasoning for attributing it mostly to adipokines when you have repeatedly shown in other posts that its pathogenesis includes multiple factors like insulin resistance, lipotoxicity and nutrient deficiencies?

Respectfully, I feel as if you're becoming a monomanic in love with his own hypothesis. Even the most rational scientists can let it happen when they perceive the potential for glory. It's not a useless theory, in fact the opposite, but let's keep our language accurate.

Hi Matthew,

I think one issue to keep in mind is that stevia tastes like crap, whereas sugar tastes good, haha. I'm exaggerating of course, but stevia is not as nice of a flavor as real sugar, and who knows how rodents perceive it. Other artificial sweeteners that taste more like sugar, like aspartame, do promote increased food intake and weight gain in rodents, at least under some conditions.

http://www.proteinpower.com/drmike/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Meta-analysis-of-low-carbohydrate-diets.pdf

Hi Gunther,

Think about it this way. Insulin signaling depends both on the amount of insulin and the degree of sensitivity of cells to the insulin. In insulin resistance, you simultaneously have higher insulin but lower sensitivity, so why would you expect insulin to suppress lipolysis (fat exiting fat tissue)?

If you look at actual lypolysis rates in the obese (who are typically insulin resistant), you find that they're actually higher than normal, although lower per unit fat mass. CarbSane has commented on that in the past. So in an absolute sense, there's actually more fat exiting their fat depots than a lean person.

The problem is, it mostly gets re-incorporated into fat tissue after it leaves rather than getting burned. That's also modulated by insulin. My point is that if you want to say anything about how insulin's effect on lipolysis influences fat gain/loss, you would have to show that the net flux of fat into/out of fat tissue is altered in people who are insulin resistant. But an easier way to do that is to just see if people who have high fasting insulin are resistant to losing weight. It appears they are not, so I don't understand the rationale for thinking insulin resistance prevents fat loss.

I think the reason very low-carb ketogenic diets cause fat loss is the same reason extreme low-fat diets cause it: they have a greatly reduced reward value. Both diets also introduce some degree of metabolic inefficiency (e.g., making ketones from fatty acids), so that may help as well by effectively increasing energy expenditure.

Stephan, about the study of the paleo diet vs the mediterranean one, I have a doubt. Why would the mediterranean diet be much more rewarding than the paleo diet?

"http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21118562"

"or a Mediterranean-like diet (n = 15) based on whole grains, low-fat dairy products, vegetables, fruit, fish, and oils and margarines during 12 weeks" I don't know how rewarding such a diet would be. Specially compared to a diet of so called junk-food. Do you have more data of that diet? I wonder if food reward can explain most of the difference between that diet and the paleo one, unless factors like opioids or other things in grains and diary had an influence. What's your opinion?

Many thanks Stephan for your detailed reply. What we need now is to hold a debate between you, Hyperlipid Peter and Taubes on this very issue!

Stephan, the fact that you are young and relatively healthy may be factoring into this discussion. You are still at an age where you can switch back and forth from glucose to fatty acids for fuel.

You said, "But an easier way to do that is to just see if people who have high fasting insulin are resistant to losing weight. It appears they are not, so I don't understand the rationale for thinking insulin resistance prevents fat loss."

Yes, people who have high insulin levels, are insulin resistant and possess excellent self control can still lose weight. However, "From a whole body perspective, insulin has a fat-sparing effect. Not only does it drive most cells to preferentially oxidize carbohydrates instead of fatty acids for energy, insulin indirectly stimulates accumulation of fat in adipose tissue." (Quote taken from http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/endocrine/pancreas/insulin_phys.html )

What that means in a practical sense is that in some people with high insulin, as soon the carbohydrate portion of a meal has been burned or stored, the hunger signal resumes. The body has plenty of adipose and free fatty acids to call upon, but it resists doing that. And in a culture where food is abundant and easily obtained, the easiest thing to do is simply to eat more carbohydrate and thereby keep the hunger signals at bay for a few more hours. The cycle repeats itself throughout the day and sometimes happens at night as well. Free fatty acids stay high, and adipose volume increases, but from the standpoint of the metabolic system, these resources will only be utilized in a very minimal way.

For people like this who lack willpower, an alternative approach is the near elimination of dietary carbs. The body is forced to use ketone bodies and free fatty acids for energy, and is finally able to utilize its own adipose stores as well.

Hi Stephan,

Is there a difference between these two hypotheses?

1) eating non-rewarding food lowers setpoint and thus, lowers bodyfat.

2) If you eat non-rewarding food, you will eat less (i.e., it doesn't taste as good so you eat less) and thus bodyfat is lowered.

Hi Stargazey,

What matters is not just the amount of insulin floating around, but the insulin signal that the cell is receiving, which also depends on the cell's degree of insulin sensitivity. So I think it's wrong to assume that high insulin in an insulin resistant person will inhibit lipolysis and favor fat gain. And in fact, the evidence appears to show that fat is exiting their fat tissue just fine.

Hi JD,

It's a fair question. Yes, there is a difference. Hypothesis (2) would predict that bland food would lower calorie intake equally in obese and lean people, whereas (1) would predict a large drop in the obese and no (or much less) drop in the lean. I feel that (1) fits the evidence better.

There is an alternative hypothesis (3) that would also fit the evidence though. That would be that lowering food reward decreases appetite/food intake only until a person is lean, at which point an anti-starvation homeostatic mechanism kicks in. In other words, the homeostatic system vigorously enforces the lower bound of body fat but food reward determines the upper bound. In my mind, that's the most plausible alternative hypothesis. A lot of people believe that's what's happening.

I feel that the hypothesis I've described fits the data a little better, but only time will tell which is correct. I would be perfectly happy for either one to be right, since they both suggest similar solutions to the obesity problem.

@Stargazey

Insulin does indeed stimulate the body to store fat and burn glucose, but people with high insulin levels are insulin *resistant*, which means this doesn't occur effectively.

"The body has plenty of adipose and free fatty acids to call upon, but it resists doing that."

No, it's just the opposite. If the body is resistant to insulin, and if insulin stimulates it to store fat and burn glucose, then when the body is resistant to insulin, it is resistant to storing fat and burning glucose. If cells were burning carbohydrate effectively, why would people have a high blood sugar problem? The issue is exactly that they are not. Stephan has indeed pointed out that people with metabolic syndrome have higher, not lower, levels of free fatty acid available for burning in their blood, even when insulin levels are high, which is exactly what you would expect if they were insulin *resistant*, that is, insulin can't keep fat properly stored inside fat cells.

Stargazey, Stephan, & Mirrorball,

With respect to the circulating insulin/insulin sensitivity issue, are we not forgetting different cells being resistant at differing rates, i.e. fat cells resisting late in the game?

Would this notion rectify these two seemingly opposing sides of this complex matrix a bit?

**********************

It's great to see a alternate idea - especially from such a profound thinker, but personally, I might agree with Stargazey to some extent: the Stephan's youth, vitality, and resilience may be getting in the way a bit here. However, since I don't know him personally, it may be out of line to state such a possible opinion.

Coming from an older, metabolically disturbed being from my youth, I'd merely like to be productive in furthering our collective knowledge.

Good job to all who help drive this clunker.

-Al

Stephan,

Great series as usual.

Where does protein fit into all of this? If umami is one of the tastes that signifies reward, what does the research show regarding high protein vs. low protein diets ... especially in context with fats and carbohydrates?

Keep up the great work.

@berto

Articles such as this one, this one and this one suggest that the problem begins with fat cells.

With respect to the circulating insulin/insulin sensitivity issue, are we not forgetting different cells being resistant at differing rates, i.e. fat cells resisting late in the game?

Yes, berto, you're exactly right. I forgot that some people don't know that. I probably should also mention that I'm not talking about dishes of cells, genetically-engineered rodents, or even humans in short-term studies. I'm talking about humans who develop prediabetes and diabetes over time.

As our muscle cells become insulin resistant, it is possible to drive glucose into the cells through increased exercise. However, as liver cells become insulin resistant, the picture gets worse. The liver finds it more and more difficult to shut off gluconeogenesis in response to insulin, and blood sugar rises. Of course the pancreas can compensate by putting out more insulin, and the liver will respond.

However, if adipose cells are still insulin responsive, they will demonstrate the phenomenon I described before: From a whole body perspective, insulin has a fat-sparing effect. Not only does it drive most cells to preferentially oxidize carbohydrates instead of fatty acids for energy, insulin indirectly stimulates accumulation of fat in adipose tissue.

The period I was talking about was when liver insulin resistance was getting started (hence, elevated glucose) but fat was not being used efficiently as a fuel because of elevated insulin levels.

Attitudes to food and the role of food in life in the U.S.A., Japan, Flemish Belgium and France: possible implications for the diet-health debate http://bit.ly/m1FoID

Mirrorball/Stargazey,

Thanks for the articles.

Actually, this change to the framework makes sense without changing results:

If adipose tissue is first to become IR, and fatty acids continue to be released (and not locked away), there is obviously some mechanism that is still accumulating fat mass.

Moreover, other less IR body cells would preferentially use glucose for fuel in the environment of increased circulating insulin, keeping fatty acids circulating freely through the blood and adipose tissue.

You can't have it both ways. If adipose tissue grows IR last, fat is "locked away"; if adipose tissue grows IR first, other tissues do not use fat for fuel - or maybe I have something wrong (I'm a simple undergrad)?

Maybe Stephan is onto something with respect to impacts upon the brain. If the dysfunction is in the adipose tissue itself, causing all kinds of downriver disruptions, maybe leptin signalling has some play here too (in our new framework) different then we originally thought.

Lastly, there is something very different between lean, just beginning to gain weight, overweight, and obese folks; and these differences may be characterized by differing system dysfunction/circulating serum levels at different stages.

-Al

Erto, the crew over at Peter's Hyperlipid blog are discussing this under a blogpost about LIRKO mice (2).

Gunther gatherer has said at 6:43 PM:

If you look at actual lypolysis rates in the obese (who are typically insulin resistant), you find that they're actually higher than normal, although lower per unit fat mass. CarbSane has commented on that in the past. So in an absolute sense, there's actually more fat exiting their fat depots than a lean person.

The problem is, it mostly gets re-incorporated into fat tissue after it leaves rather than getting burned.

I don't have a reference in a physiology text for that, but it makes sense. Insulin resistance isn't an on/off switch. It's more of a rheostat. Insulin sensitive fat cells don't shut the door completely on lipolysis in response to insulin, but they do perform less lipolysis per unit of fat mass. However, as the total fat mass increases, the total amount of lipolysis (and circulating free fatty acids) is greater.

The problem is that, in the presence of all that insulin, cells will preferentially use glucose for energy (remember, muscle cells don't need to be insulin responsive to take up glucose), and most of the free fatty acids will float around until they are reincorporated into fat deposits.

@Stargazey: I would say that *many* FA's get taken back up by adipose tissue, but the elevated circulating FA's mean that ectopic tissues take them up too. They can't refuse! This leads to increased myocellular lipid content. That per se doesn't seem to be the issue, it seems by all indications to trace to the "backup" if you will of ceramides and diacylglycerol: lipotoxicity.

This notion of insulin resistance beginning in the periphery is attributed to a one HYPOTHESIS of Neels' highlighted by Taubes. The body of the evidence is that pathologic (as opposed to physiologic that can be induced by fasting, high fat consumption or excessive fructose) IR begins with the fat.

Stargazey, the quote you cite are not my words, but actually me citing Stephan here above.

Stephan, do you have a universal definition of what tastes "good"? I love fermented cream and my girlfriend hates it. Is it going to make me fat and my girlfriend skinny?

In fact, I've been eating it since the beginning of going VLC, and despite my love for it, it helped me to never be hungry? According to Food Reward Theory, how can this be?

Gunther gatherer, oops! I missed that. But if I'm quoting Stephan, that's even better.

@berto

What Carbsane said. The metabolic syndrome begins when fat cells are no longer keeping fat locked away in the presence of high blood sugar/insulin. Excess free fatty acids in the blood interfere with glucose metabolism so that cells would burn *fat*, not glucose, unless the pancreas secretes large amounts of insulin to compensate for this insulin resistance. It doesn't make sense to me that insulin resistant cells would preferentially use glucose for energy. If it were true, they would be insulin sensitive, not insulin resistant, and the pancreas wouldn't need to secrete excess insulin.

Hi Stefan,

All this research is fascinating, but isn't it true that when someone attempts to become healthier through diet or whatnot, in essence they are trading one reward for another (that sweet candy high for a feeling of power endowed by a healthy metabolism)? I'm just wondering if maybe you could explain how someone with a more deformed metabolism is supposed to transition from an instant gratification towards one that is beyond the outskirts of the city they've lived in their entire lives.

Really enjoy your blog!!

Stephan wrote:

"Think about it this way. Insulin signaling depends both on the amount of insulin and the degree of sensitivity of cells to the insulin. In insulin resistance, you simultaneously have higher insulin but lower sensitivity, so why would you expect insulin to suppress lipolysis (fat exiting fat tissue)?

"If you look at actual lypolysis rates in the obese (who are typically insulin resistant), you find that they're actually higher than normal, although lower per unit fat mass. CarbSane has commented on that in the past. So in an absolute sense, there's actually more fat exiting their fat depots than a lean person."

Thank you for confirming that I am not insane, trying with complete futility to understand how anyone can think that high insulin is suppressing lipolysis in obese people, thus leading to obesity, when they have high free fatty acids. Perhaps I can't understand it because it doesn't make any sense. :)

Chris

@ Mirrorball,

We agreed that if IR begins at adipose tissue, other tissues would still be sensitive, therefore accepting and preferentially using glucose for fuel. Like I said, you can't have it both ways.

@ Stargazey,

That's what I was getting at. Even if IR begins with adipose tissue, and it freely gives up fatty acids - what is going on at the inlet? Possibly more fatty acids entering adipocytes, resulting in net increase?

Also measuring the already obese (once they have reached adipose equilibrium) may not reveal the same serum hormone levels as other persons at different stages in weight gain, which is why I mentioned that as well.

@ Carbsane,

Assuming IF does begin at adipose tissue, and even when lean begins an increase in adipose mass, what is the mechanism for net adipose mass increase, and why does a carb reduced diet counteract this mechanism?

I'm not trying to defend a theory, and apologize if you have answered this elsewhere.

@ Chris,

Do we see high circulating FFAs only in the obese, or also in those who are just beginning on their path towards obesity? Also, if you would, you can address some of the concerns I have commented on above.

Thanks.

Respectfully,

-Al

Hi Stabby,

What I said is that food reward is "a dominant factor", not "the dominant factor". There's still room for the idea of leptin resistance and other disturbances in the homeostatic mechanism, and in fact that's mostly what I'm working on in the lab.

The food reward idea does not invalidate other hypotheses.

Hey Al,

I'll be blogging on this topic slowly over time. :)

Chris

@berto The idea is that when fat starts "leaking" out of fat tissue, it causes insulin resistance in other tissues. AFAIK you can't have high free fatty acid levels and have muscle/liver cells remain insulin sensitive.

Wow...so many of the comments here are confusing taste with food reward. They are NOT the same thing, folks. Food reward is a psychosomatic (aka mind/body) dynamic where the brain creates a taste-calorie connection through repeated exposure to a food.

In other words, even if you don't "like" something you can still end up creating a taste-calorie connection if you eat that food enough times. When this happens you will suddenly find yourself "liking" that particular food. Whether or not you "like" a food has nothing whatever to do with personal taste. It has everything to do with whether or not your mind has been conditioned to understand that this food contains things that your body wants. The more concentrated nutrients it contains (whether macro or micro), and the longer you've been exposed to it, the more you will "like" it.

If you've never been exposed to a food, and if its taste/texture/aroma is radically different from anything that already exists as a taste-calorie connection in your brain, then you will most likely find it disagreeable or even disgusting upon your initial exposure. It isn't because "you" dislike it...it's because your brain is telling you to dislike it because your brain doesn't yet know better.

Example: a good friend of mine started eating a fruit from southeast Asia, called durian, not too long ago. He did this on recommendation from another friend. At first he hated it. It smells horrible, has a strange appearance, unusual texture and a much different taste than anything he was used to eating. However, he forced himself to eat this fruit every day for about two weeks or so. At some point towards the end of that time something switched in him. He suddenly began to absolutely love eating this fruit. In fact he craved it quite intensely.

What happened? Did he "get used" to the taste? Of course not. His brain began to understand that this particular taste/texture/aroma combination was immediately followed by an influx of calories and nutrients that were beneficial to the body. A taste-calorie connection was formed and his brain flipped on the "like" switch. Now, unless he has repeated exposure to negative associations with durian for some inexplicable reason, he will "like" this food for the rest of his life. I, on the other hand, refused to eat durian no matter how much I was pressured to try it. Guess how much I "like" durian? Not at all. I find it disgusting. Or I should say, my brain has not yet learned just how beneficial durian is.

The author of the Shangri-La Diet learned how to trick the brain into lowering the body's fat mass set point by providing it a certain amount of tasteless calories using light olive oil or sugar water. It won't work with extra virgin olive oil, however, or with sugar water with lemon juice added. Why? Because after a couple of weeks the brain forms a taste-calorie association and the gig is up. It begins to crave that particular taste/texture/aroma because it knows it is immediately followed by calories and other nutrients.

Lastly, this also explains why stevia will not cause rats to gain weight when added to their food whereas sugar will. After consuming stevia there is no immediate influx of additional calories, therefore no taste-calorie association is formed in the rats' brains. Additionally, the brain does not perceive "sweet" by itself as a flavor. This is why the Shangri-La Diet author was able to drink sugar water and lower his body's fat mass set point. If the sweetness is not connected to an influx of otherwise flavored calories the brain does not make the connection.

So how do we lower our set point without resorting to tasteless oil or cups of sugar water? By eating whole, natural foods that have very little or nothing at all added to them and which are consumed in their natural unprocessed forms. The less intense the flavor profile the weaker the signal to the brain. This is the reason fast foods and highly processed foods can be so addictive. They unnaturally ratchet up the flavor/texture/aroma signal to unheard-of heights and practically overwhelm the brain with a massive taste-calorie association that never existed in human history.

Call it "bland" if you like, but prior to the modern era there didn't exist an unnaturally exaggerated taste-calorie association being created in the human brain to sit in contrast to the natural taste of whole foods. Natural foods can't be bland unless you're comparing to unnatural man-made concoctions, additives or processing.

Derek,

I"m really confused as to your rationale regarding the psychosomatic reaction. I"m pretty sure in part two where there was mention of the feeding of bland food causing reduced calorie intake. If it had to do with nutrients and whatnot within the mixture that caused the reward then there should not have been any reduction in calorie intake, i think......

Stephan and Chris,

Stephan said that FFAs are higher in obese but lower per unit fat mass. To me that does imply the insulin (or something else) is preventing lipolysis. I don't like to speculate about what the body is "trying to do," but wouldn't we expect more fat conservation in lean people? The opposite happens.

@john

What matters is the absolute amount of FFAs. There are already more FFAs than the body can burn; if insulin weren't preventing lipolysis somewhat, all cells would be drowning in fat, which would increase lipotoxicity even more.

Hmm, have there been any prospective studies that looked at FFAs and/or fasting insulin as a predictor of obesity?

Might-Al,

Keep it coming. I'm very interested, and trying to digest.

Thanks.

-Al

@ Might-o'chondri-AL

What you just outlined is the exact process I've gone through in the last 18 months.

I started out pre-diabetic with HbA1C of 5.8 and fasting glucose of 120.

A regular exercise regimen of weight training with compound movements (deadlifts, squats, pulldowns, rows, bench press, shoulder press) combined with wind sprints multiple times weekly, has changed my metabolism.

My HbA1C is now 5.0 and fasting glucose 90. Of course to achieve these results I had to push myself to exhaustion consistently and do so over a period of a year and a half. I also changed my eating habits, but I had changed eating habits previously without adding the intense, regular exercise and saw only minimal results. Intense exercise using all the major muscle groups in the body is a MUST for repairing the metabolism, just as you state.

My goal a year from now is 4.7/80 and I know that's achievable.

@john See Carbsane's blog. For a start:

http://carbsanity.blogspot.com/2011/03/fasting-insulin-weight-loss.html

http://carbsanity.blogspot.com/2011/04/fasting-insulin-weight-loss-ii.html

i'd like to add another consideration, based on lectures given by donald layman at the last 2 regional bariatric physicians meetings:

prior to age 25-30, insulin is a GROWTH HORMONE, i.e. it stimulates PROTEIN SYNTHESIS, and the efficient incorporation of dietary protein in new muscle, enzymes, etc.

further, giving 2 groups of lab rats IDENTICAL, fully nourishing diets with the protein distributed differently produces different results. 1 group got its protein in a small quantity at breakfast, a moderate quantity at lunch, and a large quantity at dinner. the other group got the SAME TOTAL PROTEIN, but in equal quantities over its 3 meals. in 6 weeks the 2nd group had higher lean body mass and lower fat. conclusion: subthreshold quantities of protein are just burned for calories, and thus reduce metabolism of carb intake, so producing more fat. turns out the signal is leucine in sufficient quantity. or insulin if you're young enough.

Mirrorball,

I know of her blog--not sure what you're getting at. What if we looked at FFAs per calorie expended?

Male athletes tend to have higher respiratory quotients than females (I think). Do non-diabetic obese have higher or lower?

@john The article below says that "severely obese patients with type 2 diabetes had higher RMR than those without diabetes":

http://www.nature.com/oby/journal/v12/n5/abs/oby2004101a.html

I don't know about FFAs per calorie expended, but why would that be important? Not sure what you are getting at either. :)

Mirror,

...Well when I first read what Stephan wrote, my initial thought was, "Okay, so they actually are having trouble doing lipolysis, sort of." You said it's the absolute FFAs that matter, but just saying it doesn't resolve the ambiguity. So, I'm wondering why it makes sense to say that fat people are fine at lipolysis when their fat breaks down at a slower/lower rate. Like you said above, you can't expect an obese person to have proportional lipolysis because of lipotoxicity issues. Are their bodies "choosing" to restrict lipolysis for that reason, or are they having trouble breaking down and oxidizing fat?

@john: I don't think it's controversial to state that our bodies generally want to store fat in adipose tissue. I think it's also pretty much agreed upon that small adipocytes are more insulin sensitive than larger ones. The increased insulin is to try to keep the NEFA delivery to normal. Yes, this is to reduce lipolysis in the fat cell, which from a health POV is what you want. Unfortunately the insulin resistant adipocyte has inappropriately suppressed HSL. There's lots of lipolysis going on!

@berto: I've blogged on adipocytes remaining sensitive to ASP (http://carbsanity.blogspot.com/2010/12/asp-pathway-and-regulation-of.html), even becoming more sensitive, as they get larger while becoming less sensitive to insulin. I think of it like a bathtub. A person in energy balance has a leaky drain and periodically adds water to keep the tub at a proper level. The obese person's drain is actually partly open so more drains out, but if they periodically add more water from the faucet, the bathtub continues to fill.

The bathtub analogy is interesting.

What if we knock out the insulin receptor completely in the adipose tissue of mice? Their fat tissue would certainly be insulin resistant while the rest of their tissues would be insulin responsive.

Fat-specific insulin receptor knockout mice have a 50 to 70% reduction in fat mass throughout life, are healthy, lack any of the metabolic abnormalities associated with lipodystrophy, live longer than control mice, and are protected against age-related deterioration in glucose tolerance.

http://130.15.90.245/biol430_2003/bluher%20et%20al%202003.pdf

This is unrelated to this post. I have a question about gut health. I have seen the recommendations you have on this site, but what would you say to someone without a colon and only their small intestine? Obviously gut barrier function is still important so probiotic foods are important, but do the types of probiotics one supplements with change, and will fermentable fibers and things like supplemental inulin not play as big of a role since their is no colon to ferment in?

John,

The issue of how to express lipolysis rates and to address whether they are higher or lower in obese people, and to what degree they are sensitive to insulin, deserves a lot of quantitative analysis of primary literature that I haven't done yet.

However, on a very basic level, I agree with what Mirror said about the excess over capacity. A great deal of these fatty acids are getting reesterified by adipose, liver, and other tissues. This shows that lipolysis is exceeding the capacity to oxidize and utilize the fatty acids. Thus, lipolysis is not rate limiting for fat loss in obese people, and insulin suppression of lipolysis is not the bottleneck in the system.

Chris

Seems like the pattern is this - switch to low fat - lose some weight, plateau. Switch to low carb, lose some weight, plateau (perhaps after a longer period).

Doesn't this pattern fit in with seasonal eating? In the spring/summer months, HG's would naturally eat much lower fat because fruits & veggies are much easier to consume, and then they would switch to low carb in the winter when animals would become the main food source.

Keep switching between low carb and low fat every 6 months, no wonder these people were all thin!

Stephan said "...when I can use much better data from a meta-analysis of many low-fat studies?"

There is a huge problem of using meta-analysis - Which studies to include? - and invariably the criteria is set AFTER the studies are picked. Any time I see a meta-study - I consider it likely junk science.

Do see Lustigs lecture

http://www.uctv.tv/search-details.aspx?showID=16717

Also, Taubes is correct that looking at calories/in/out misses the big picture:

Appetite ultimately controls calories in - or people would have long term success with low calorie and low fat diets (most don't).

So what can we do to reduce appetite?

- No sugar foods - low carb diet

- No MSG or flavor enhancers

Please don't miss the key point that a low carb diet is much easier to stick to because it reduces appetite!

That people might spontaneously reduce calorie intake in response to a(n unpalatable) low fat diet seems plausible enough. That people would spontaneously eat less eating either low fat or low carb compared to the most palatable high carb and fat 'cafeteria'/'dessert'/SAD diet also seems plausible.

That people are reducing their intake of calories on a high fat low carb diet because the diet has low food reward seems a bit trickier. I can at least see the potential for this to be true, contra the mainstream wisdom that high fat = highly palatable. I, for one, find plain butter (or esp. dessicated coconut meat) to be bland as anything. However, this theory does seem to be difficult to reconcile with a very basic observation of low carb dieting. Paradigmatically, people lose a lot of weight when first starting low carbing 'despite' merrily eating only steak with melted camembert poured over it, washed down with some cream. These people are both simultaneously very full and loving the food. It would seem that they find the food highly rewarding. Notoriously, a lot of low carbers find that the diet becomes less satisfying after a while, that steak and cream lose their savour and that the weight stops coming off. Strikingly though, their ceasing to find the food rewarding seems to come at the same time that they feel the need to eat more and more of it to be satisfied. On the food reward hypothesis, it'd seem that we should expect people to feel compelled to eat more at the beginning of low carb and decrease their intake as they get bored, whereas, in fact, we see the reverse.

Obviously we need to be wary of equating food reward with simple tastiness. We should think that there are different sorts (hedonic vs homeostatic) of hunger, but I think that the story told in the post about low palatability low carb/low fat need to take account of these.

Karl,

I agree that ideally studies should be evaluated individually rather than only relying on meta-analyses, but in a meta-analysis the authors describe their methods, and in a quality analysis this generally includes having two or three people select the studies based on fixed criteria, resolve disputes through discussion, and sometimes assess study quality in a blinded manner. It is of course possible that they are committing research fraud, which is a genuine problem, but that is also true of any of the individual studies. The inevitable result of accusing people of research fraud without direct evidence is that one can select which evidence to believe based on whether it fits one's hypothesis, which is tantamount to ignoring the evidence entirely.

Chris

@john

I get it now. I think the study I mentioned suggests that diabetic people are fine at lipolysis.

@Stargazey

Interesting article. It seems insulin's supression of lipolysis isn't as important as is being lean, because the FIRKO mice have normal FFA levels (unlike obese/diabetic humans), thus no lipotoxicity. They also have very high leptin levels. I don't know what that means. OTOH, in studies such as this one, researchers prevent fat cells from storing fat and the result is insulin resistance, especially in db/db mice, which overeat because they have a mutation in leptin receptors. The plot thickens! :)

Hi Karl,

I think there are pitfalls with meta-analyses, and there are also pitfalls with individual studies. I don't think it's a good idea to dismiss all metas as junk and then use a single hand-picked study to support a point instead, when there are many others out there.

I agree that low-carb diets reduce appetite. My point is that low-fat diets do as well, as do vegan diets and paleo diets. Otherwise, why would people eat fewer calories when they're not asked to? Studies that have looked into it suggest that they're eating to fullness.

My general impression is that adherence rates tend to be a bit better on low-carb diets than low-fat. LC may, as you said, be easier to maintain for the average person.

I also agree with your point about sugar and MSG; those are highly reinforcing foods as both rodent and human studies have demonstrated. Sugar rapidly produces addiction-like behaviors and brain activity in rodents, and I'm pretty sure it can in certain people too.

Stephan's article shows how complex the subject of obesity really is.

The Caloric Hypothesis is dead. it is much, much too simplistic to explain obesity. Science has turned up many new things, none of them behavioral.

@ Stephan (Or Anyone TBH)

Thanks for the great insulin post to Gunther. I too had that question!

It was my naive understanding that insulin resistance caused fat gain via inhibition of lypolysis and an increase in lypogenesis. But you turned my thinking on its head, from what I can gather in your comment, are you saying that;

If the cells are resistant to insulins "glucose taking" action then similarly they should be resistant to its lypolysis/lypogenesis action? Which you demonstrate by showing that type II's still have high rates of lypolysis.

That makes sense to me to an extent. Do you believe that insulin has no bearing on fat gain? Ie take a lean person and ruin their insulin sensitivity with low sleep/magnesium/sugar/stress/cortisol and surley their body comp will shift to fat over muscle?

I realise that leptin is a big player in appetite and "bringing the calories in" as it were, but I always thought where those calories GO was insulin and insulin sensitivities job

My little brain is spinning, thanks in advance for a response if you get the time,

Hello - Chris Masterjohn & Stephan

About meta-studies. Good science is tricky and really hard work - (I have not looked at the paper you are talking about - I'm speaking only about science.) It is possible to craft a good meta study - but what I see is data collected under differing methods and criteria combined ends up being often miss leading rather than illuminating. Sadly, there are way to many poor quality studies and combining 5 poor quality papers with one high quality paper just ends up diluting the good study.

And it is possible that one good study can refute several others. Consider diet surveys: there was a study out in California that basically showed that people, don't remember what they eat, make bad estimates, lie and that such studies are systemically flawed, yet they continue. Compare several diet survey studies with one well conceived and executed controlled diet study and

I'll take the good study.